Crossbill Evolution

by Michael K. Schwartz

Broadcast 6.2 & 6.5.2020

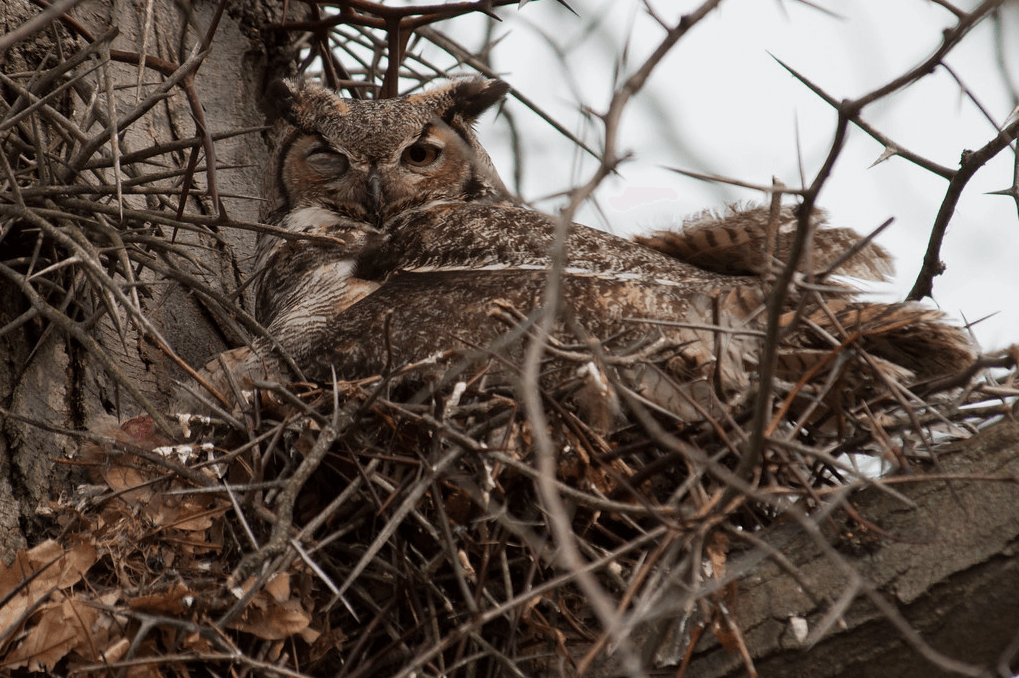

Photo by Elaine R. Wilson, www.naturespicsonline.com (CC 3.0).

Listen:

As winter faded into spring and the last remnants of snow remained in shadowy patches atop higher peaks, I wandered into the Rattlesnake Wilderness, outside of Missoula, Montana. The air was filled with male songbirds singing to attract a mate for the season. The crackling call of the corvid, the rasp of the chickadee, and the delicate honk of the Red-breasted Nuthatch were giving way to the springtime calls of warblers and thrushes.

As I crossed an open meadow to begin an ascent of a nearby peak, the air became dizzily filled with the spirally calls of Pine Siskins. I climbed for hours, listening to the crackling air fill with renewed voices while watching the dashing and darting of small bodies through three-dimensional space. Despite all of this cacophony and confusion, the sounds from one lodgepole pine were slowly becoming exceptional. As I approached this particular conifer I saw nearly fifteen yellow and red birds feeding on the old sealed cones. Although many of the cones remained affixed to the branches, others, having been clipped from their winter perch, clinked and popped as they rained to the ground.

I pulled my binoculars out from under my jacket, and sure enough identified this group as a flock of Red Crossbills. How could I be so sure? For those who have not seen the crossbill, its lower mandible doesn’t evenly match to its upper mandible. Whereas most birds have bills that match like a pair of pliers or tweezers, the crossbills’ are more like a pair of curved scissors. As I watched and listened to the aerial circus, I began to wonder about this malformation of their beaks. Was this an evolutionary adaptation or a recurring genetic error?

For the French naturalist Buffon in the 1800s, the crossbill’s beak was “an error and defect of Nature, and [a] useless deformity.” Since Buffon’s time, it has been suggested that the crossing of the bill is not a deformity but rather an adaptation to assist in seed husking.

However, Craig Benkman at the University of British Columbia, who has studied this bird and its unique bill, found that crossbills without the hooked beak husked seeds at the same rate as those birds with strongly hooked beaks. Therefore, the hook probably did not evolve for husking purposes. Benkman discovered that when crossbills encountered an unripened cone, those with hooked lower bills were able to 1) rapidly bite between the cone’s scales, 2) laterally shift the beak to separate the scales, 3) insert their tongue into the crevice, and 4) pry out the seed! Those without the hook obtained a seed, but required three times as long to do so! Thus this strange deformation is actually a fine tuned adaptation for obtaining seeds.

While further studying this adaptation, Benkman noted that some birds had bills that crossed to the left while others had bills that crossed to the right. Amazing! Like people, these birds demonstrated right and left-handedness. Were there more right-billed birds than left, just as there appear to be more right-handed people than left-handed people? Benkman guessed that the ratios would be equal because of the crossbills’ eating habits. You see, crossbills hurry from one seed to the next, leaving seeds behind. Therefore, it seemed likely that different seeds would be left by righties than would by lefties, allowing more birds to persist if there were equal numbers of righties and lefties in a population. And this is exactly what Benkman found in the wild.

So once we thought of this bird as a malformed anomaly, but through careful observation and study, we have realized its beautiful adaptations to the wild.

Every week since 1991, Field Notes has inquired about Montana’s natural history. Field Notes are written by naturalists, students, and listeners about the puzzle-tree bark, eagle talons, woolly aphids, and giant puffballs of Western, Central and Southwestern Montana and aired weekly on Montana Public Radio.

Click here to read and listen to more Field Notes. Field Notes is available as a podcast! Subscribe on iTunes, Google Play, or wherever you listen to podcasts.

Interested in writing a Field Note? Contact Allison De Jong, Field Notes editor, at adejong [at] montananaturalist [dot] org or 406.327.0405.

Want to learn more about our programs as well as fun natural history facts and seasonal phenology? Sign up for our e-newsletter! You can also become a member and get discounts on our programs as well as free reciprocal admission to 300+ science centers in North America!