Her Dream: Blackfeet Women’s Stand-Up Headdresses

By Rosalyn LaPier

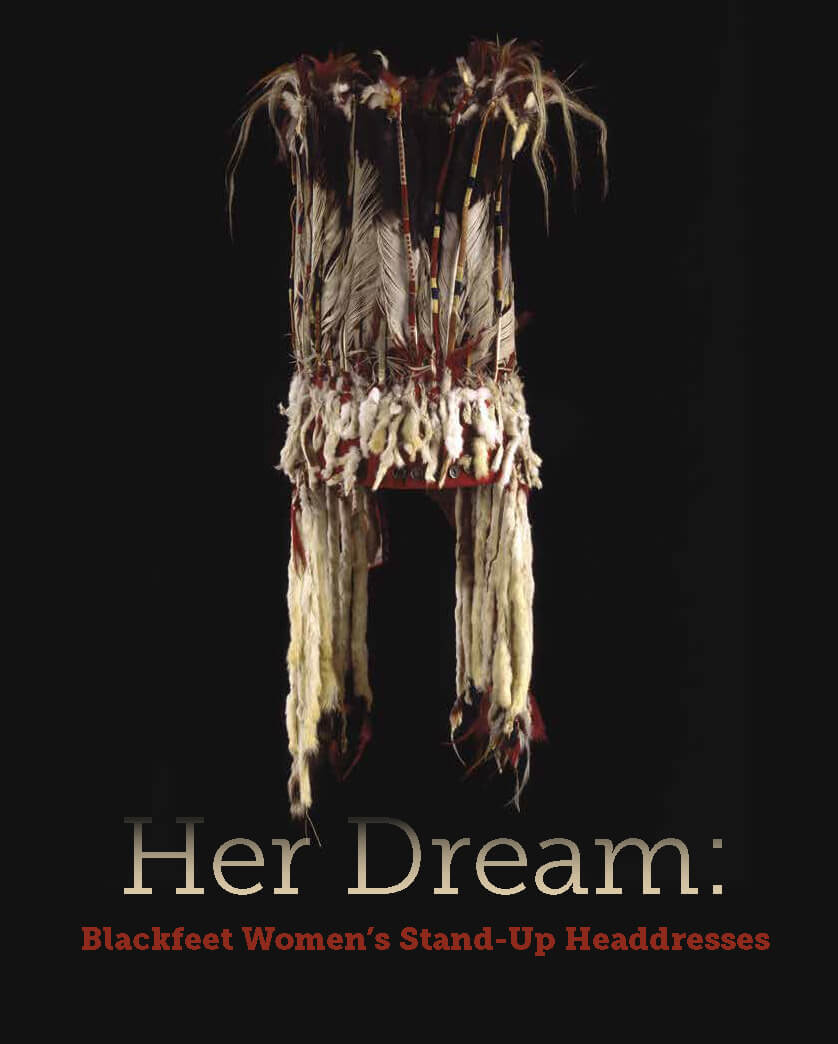

Stand-up bonnet (Blackfeet), ca. 1880. Trade cloth, Golden Eagle feathers, ermine fur, horse hair, bells. Image © Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Cody, Wyoming. Chandler-Port Collection, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Richard A. Pohrt, Sr.

When most people imagine a Blackfeet person in their regalia, they probably visualize a man wearing a large headdress with feathers sweeping backward. Would it surprise you to know that the Blackfeet historically did not wear the Sioux-style, or “wobbly” headdresses, as one elder called them? Or that it was not just men who wore headdresses, but women, too? Blackfeet women wore what are called “stand-up” headdresses. And they still do. Stand-up headdresses are very old, from “way back in history,” according to Weasel Tail, an 85-year-old Kainai man living in Browning in the 1940s. “Each one was dreamed,” he said, “and made the way [the headdresses] were seen in dreams.” Cecile Black Boy, a Blackfeet woman who also lived in Browning in the 1940s, remembers the story she learned about the original stand-up headdress.

Group of Blackfeet (Amskapi Piikani) men and women singing in front of a tipi, ca. 1913. Note the various types of headdresses, including both the stand-up and Sioux style. Photo by Rodman Wanamaker, 1863-1928, Library of Congress.

It came from the dream of a woman a long time ago.

One day a young woman went out to collect dried cottonwood branches for her fire. After she was done with her chore, she lay down to rest and she fell asleep. She dreamed that a buffalo-deity, a being from the supernatural realm, came to her and said, “Daughter, I have come to give you a headdress. But I want you to tell your people not to [kill] my children anymore.”

Stand-up headdresses are different than the Sioux-style headdresses because, as the name suggests, the feathers literally stand straight up. Each stand-up headdress looks similar but is designed and decorated a little bit differently based on the dream of the creator of the headdress.

She looked at his headdress and thought it was the most beautiful one she had ever seen.

The Blackfeet once called themselves the Saokio-tapi, or the Prairie people. They made the stand-up headdresses from elements found on the prairies that had a connection to the supernatural realm: Golden Eagle tail feathers and plumes (Aquila chrysaetos), bison rawhide and sinew (Bison bison), white or winter ermine hides (Mustela erminea), porcupine quills (Erethizon dorsatum), small pins made from willow (Salix exigua), and red ochre for paint (iron oxide, hematite).

The buffalo-deity added, “I will teach you the songs to this headdress and give you all my power to be fortunate and be blessed with a good life, if you do as I ask.”

To create a headdress the Blackfeet started with a stiff piece of bison rawhide to make a headband. The rawhide headband was then folded in half and holes were placed along the folded edge to put the hollow shaft, or calamus, of the feather through.

The calamus of each feather was reinforced with a small wooden peg made out of willow. The rachis or central part of each feather was then decorated with a thin rectangular piece of rawhide wrapped with colored porcupine quills and sewn onto the rachis. This made each feather stronger and enabled it to stand up. Some Blackfeet said the headdresses usually had 14 eagle tail feathers; others said they used more.

The eagle feathers were placed through the holes in the rawhide headband and connected inside of the rawhide with sinew. From the outside, a person could not see the calamus, just the feather sticking out of the rawhide.

The outside of the headband was then decorated with red ochre paint and white ermine skins attached on both sides near the temples, and with other decorations or designs based on the maker. After the Blackfeet began to trade with Americans, they decorated the outside of the headbands with red wool flannel instead of red ochre paint, and shiny brass tacks.

A rawhide string was added to the back of headdress to tie or tighten and then untie the headdress. When the headdress was not in use it could be untied, rolled up, and carried over the shoulder.

The young woman agreed.

She learned all the songs and ways to use the headdress from the buffalo-deity, who continued to return in her dreams until she completed her training.

The Blackfeet believe that it is important, even necessary, to create relationships or allyships with the supernatural realm. In her dream, the young woman creates a relationship with a supernatural being, the buffalo-deity, who teaches her about the stand-up headdress. She then creates the headdress using elements from the natural world.

In one version of the story, the young woman remained unmarried for many years, using the headdress herself.

However, around the turn of the last century, about the time that Browning became a town in 1895, elders said that the Blackfeet began to wear the Sioux-style headdresses.

Annie Bear Chief, a 70+-year-old elder, said that the Blackfeet were introduced to “those wobbly bonnets” when Browning grew as a town. She lamented that “our old bonnets were beautiful, straight up” and decorated with porcupine quills.

In another version of the story, the young woman was married and she told her husband of the dream. He collected eagle tail feathers for his wife to make the headdress.

After the young woman learned all there was to know about the stand-up headdress, she transferred her knowledge and the headdress to her husband and then their son.

This is how the Blackfeet believe that the stand-up headdress was introduced to them. They have always worn the stand-up headdress since they were first dreamed into existence by a Blackfeet woman; the headdress continues to be transferred or exchanged among Blackfeet women.

The transfer of a sacred object can sometimes take days or even months, because it can only happen after a person learns the story and songs of the object, as well as how to make it. Collecting the natural materials, such as the feathers, quills, or furs, can take time as well because they may come from different ecosystems on the landscape and are collected during different seasons of the year.

Three Calf, a Blackfeet elder, said that the Blackfeet readily adopted the Sioux-style headdresses because they were not viewed as sacred or connected to a supernatural ally and thus did not require a transfer ceremony like the stand-up headdress. “By the late years of the 19th century,” he said, “few people were alive who had the [supernatural] power to make the standup bonnets; and it could be made only by one who had that power.” He added that the Blackfeet believed that the “stand-up bonnets were a sacred thing.”

Betty Cooper, Michelle Eagle Plume, and Theda New Breast, all members of the contemporary Women’s Stand-Up Headdress Society. Photo courtesy Theda New Breast.

However, today there is a resurgence and revitalization of Blackfeet lifeways, food systems, language, and ecological knowledge. The Kaa-poi-saam-iiksi—the Women’s Stand-up Headdress Society—has been revitalized, with dozens of members in both Canada and the United States.

In Her Dream, as the young woman put on her headdress, it brought together two worlds—the natural world and the supernatural realm—through her dream, the story, the songs, the natural materials from the prairies, and the relationship with her ally, the buffalo-deity.

Today, many Blackfeet women are returning to wearing stand-up headdresses and bringing those two worlds together again for a source of community health and well-being.

—Rosalyn LaPier (Blackfeet/Métis), Ph.D., is an Associate Professor of Environmental Studies at the University of Montana and Research Associate at the National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution. She is the author of Invisible Reality: Storytellers, Storytakers and the Supernatural World of the Blackfeet, University of Nebraska Press, 2017.

Note: In the early 1940s ethnohistorian John C. Ewers set out to interview elders and knowledgeable Blackfeet in Browning, Montana, about the history of the stand-up headdress. The quotations in this piece all come from Ewers’ research.

This article was originally published in the Winter 2018-2019 issue of Montana Naturalist magazine, and may not be reproduced in part or in whole without the written consent of the Montana Natural History Center. ©2018 The Montana Natural History Center.

Click here to read more articles from Montana Naturalist magazine.

Want to learn more about our programs? Sign up for our e-newsletter! You can also become a member and get discounts on our programs as well as free reciprocal admission to 300+ science centers in North America!