Whitebark Pines

by Nick Voss

Broadcast 5.15 and 5.20.2016

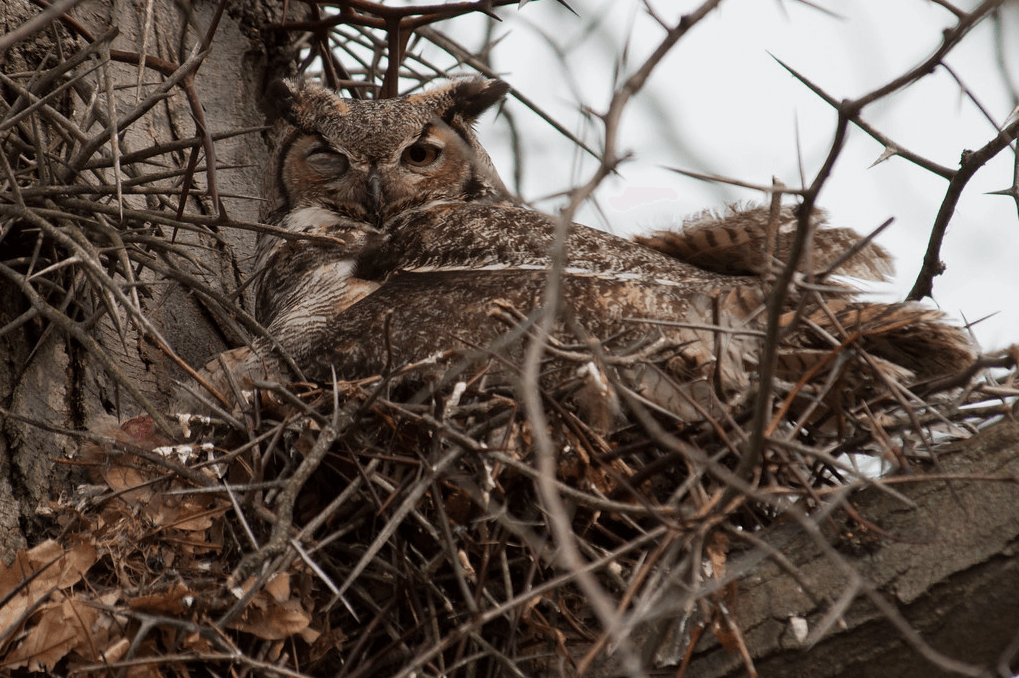

Photo by FaMartin (CC-BY-SA 3.0).

Listen:

I first visited Glacier National Park in June. Though winter had only recently loosened its grip on the Crown of the Continent, there were blue skies and sunshine as I hiked up a high-elevation glacial basin. The temperature was a balmy 60 degrees.

Even at the trailhead, the consequences of the harsh winter were clear. The only trees to be seen were subalpine firs, whose profiles rose like needles, to best bear the brunt of tens of feet of snow.

As I went higher, the forest thinned out into dense clusters. The trees became shorter, and the branches thicker and closer together to stave off 100 mile-per-hour winds, freezing temperatures, and avalanches.

By 7500 feet, the trees carpeted the ground, rarely able to even grow above head height. The only animals to be seen were small birds and a rare squirrel. Up here, winter conditions were pushing life to its limit.

However, over the last hill before the end of the basin, the scene changed dramatically. Before me was not windswept rock and shrubbery but a primordial forest of stout, old trees. A curious ashy-gray bark covered their tremendous trunks, which towered up to thirty feet over their surroundings. Birds sang all around us. Squirrels scurried across the trees. There were grizzly tracks in the mud. This was a whitebark pine forest, an oasis of biodiversity in a near-barren landscape.

The seasonal variation near the tree line is brutal. Winter is blisteringly cold and long, winds are high, and avalanches can level entire forests. The warmer months are nearly bone-dry, and the growing season is very short. It is a wonder that whitebarks can grow in such a place; and they certainly couldn’t if it wasn’t for a very specific set of adaptations.

Whitebark pine grow stout, compact, trunks and branches to conserve water and combat frostbite. To bear the brunt of high winds and heavy snow, the wood is very dense. It is also packed with resin to resist insect attack. But perhaps the most remarkable feature of whitebark pines is that since they cannot grow quickly, they grow for a very long time. They become full sized at 250-300 years, and frequently approach 900 years of age. The oldest whitebark ever found was 1267 years old, in the Sawtooth Mountains of Central Idaho.

Photo by Walter Siegmund (CC-BY-SA 3.0).

It’s not just the age of the trees that makes them so distinct. Whitebark pine is a keystone species, meaning it enhances the biodiversity of its surroundings. Its greatest contribution is its large, edible seed crop. Whitebark pines produce very large and nutritious seeds that are nearly 50 percent fat. These seasonally available nuts are important food for a multitude of animals, such as Clark’s nutcrackers and Douglas’s squirrels, which hide enormous caches under the rocks. Grizzly bears in turn use these conveniently organized caches as critical pre- and post-hibernation snacks. They are so desirable that grizzlies have been known to sniff them out from under six feet of snow!

Whitebark stands can even affect the hydrology of the area. The trees act as snow fences, which accumulate large drifts behind them in the winter. The drifts melt slowly in spring, ensuring a steady supply of water weeks longer than normal. As a physical and ecological anchor for other species, whitebarks are an invaluable species in the subalpine ecosystem.

Unfortunately, whitebark pines are under attack from all sides. White pine blister rust and mountain pine beetle epidemics driven by global warming have heavily impacted most forests, often targeting large adults. A study in 2002 found natural regeneration in only 35 percent of their range in northwestern Montana and Idaho, rendering them functionally extinct in most of their range. Many of the trees are still alive, but without the ability to reproduce, the species has no future there.

As I continued my walk among the old trees, it struck me how rare the opportunity to see a living whitebark forest may be in the coming years. These wonderful, beautiful, twisted old trees are the crown of the alpine ecosystem, but amidst the destruction of invasive species and the rising threat of global warming, even these hardy sentinels may just lose their footing.

Every week since 1991, Field Notes has inquired about Montana’s natural history. Field Notes are written by naturalists, students, and listeners about the puzzle-tree bark, eagle talons, woolly aphids, and giant puffballs of Western, Central and Southwestern Montana and aired weekly on Montana Public Radio.

Click here to read and listen to more Field Notes. Field Notes is available as a podcast! Subscribe on iTunes, Google Play, or wherever you listen to podcasts.

Interested in writing a Field Note? Contact Allison De Jong, Field Notes editor, at adejong [at] montananaturalist [dot] org or 406.327.0405.

Want to learn more about our programs as well as fun natural history facts and seasonal phenology? Sign up for our e-newsletter! You can also become a member and get discounts on our programs as well as free reciprocal admission to 300+ science centers in North America!