Pleistocene Megafauna

by Tom McKean

Broadcast 11.2013, 11.2018, and 11.15 & 11.18.2023

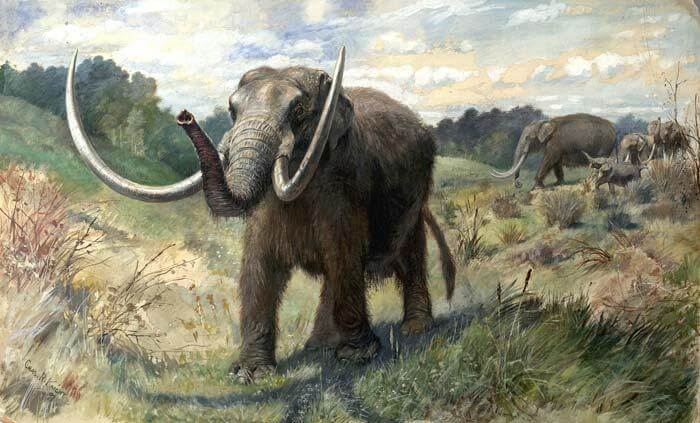

Artist’s rendering of an American mastodon. Charles Knight, public domain.

Listen:

A cheetah crouches in the tall grass. Pronghorn graze warily in the cool summer breeze. After minutes of quiet patience the cheetah erupts into a burst of muscle and speed. A small herd of pronghorn sprint into action, their nimble legs churning ground. A race for life ensues as the cheetah and pronghorn tear across the prairie. But bad luck this time for the cheetah; it retires to the shade for another hungry morning as the pronghorn dance away into the grass.

You may be wondering what a cheetah, a big African cat, is doing chasing pronghorn, an iconic North American species. Well, you may be surprised to hear that North America used to be home to many animals you would recognize only on the African savannah, and many that you wouldn’t recognize at all. This very scene may have played out in your own backyard – well 20,000 years ago, anyway. This period in North America’s history was the Pleistocene era, more commonly known as our most recent ice age.

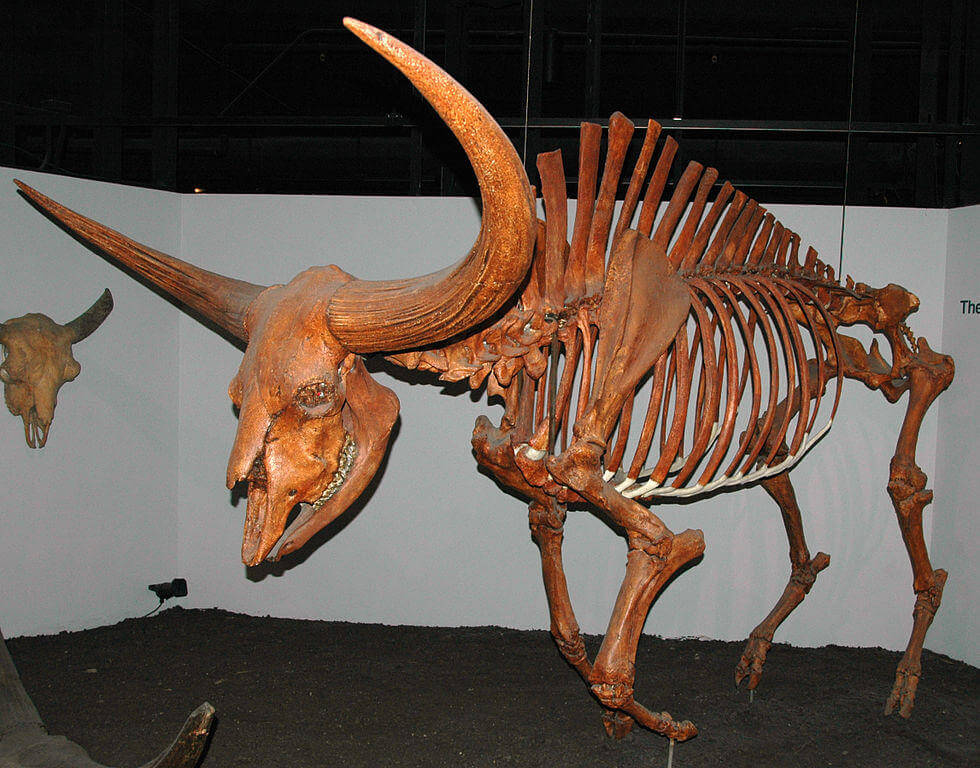

Bison latifrons fossil. Photo by James St. John (CC-BY-2).

Indulge in a flight of fancy. Imagine you’re a California condor, a huge scavenging bird. From your lofty position above the windswept plains, you can see herds of bison unimaginably larger than any congregation of the beasts ever seen in present-day Yellowstone. However, these aren’t your everyday bison. The giant longhorn bison of the Pleistocene weighed in at 1,800 pounds with horns many times the size of the plains bison we see today.

You soar over and past the bison herd. Your grumbling tummy drives you to keep looking for a tasty morsel of rotting flesh. You soar over a few megathiers, three-ton grounds sloths with giant claws, creatures so bizarre they defy description. Nothing dead here. Press on.

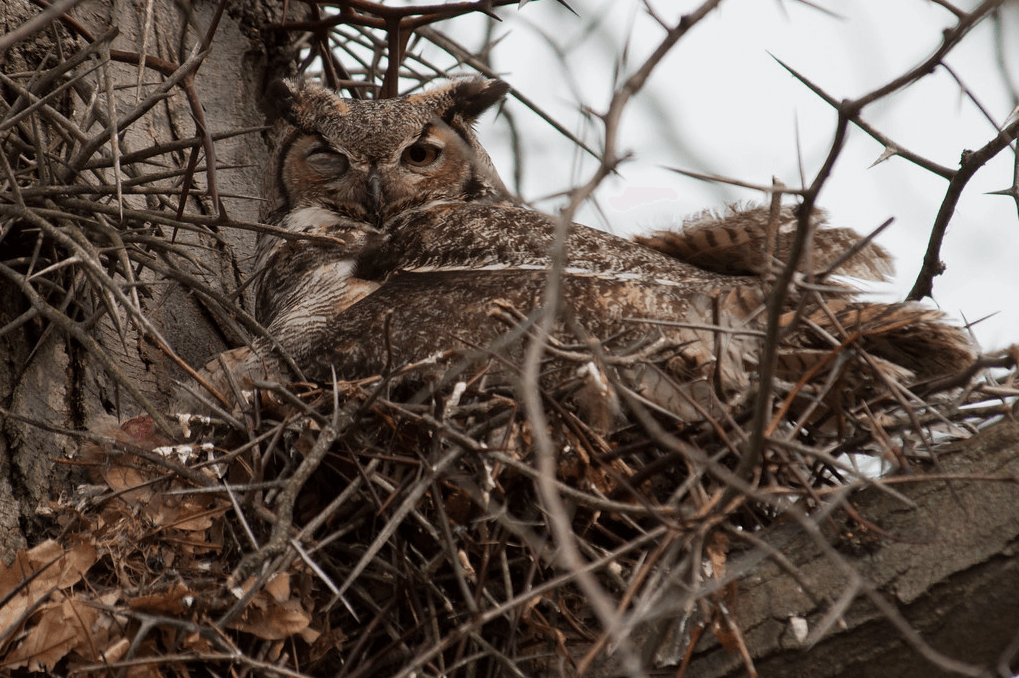

Off in the distance past a herd of woolly rhinos you see a band of stocky dire wolves trotting toward a family of mastodons. Instinct encourages you to perch high in a nearby ponderosa pine tree. The dire wolves, at first glance, don’t look much different from the gray wolves with which they share the landscape. They look about the same size, but the dire wolf is built with stockier bones and muscle, slightly larger in general. The adult mastodons make them look like toy poodles in comparison. The mastodons are very similar to modern-day African elephants, but covered in short dense hair. Like elephants, the mastodons are good parents, setting up a predator-proof defense around their offspring. Realizing the likely unfavorable outcome of their hunt, the dire wolves decide to go see what the rhinos are up to.

Your appetite encourages you to follow the wolves. But then another movement in the distance catches your attention. Your powerful long wings heft your body back up into the clear sky and your keen vision immediately focuses on a giant short-faced bear on a fresh bison kill. Standing tall at just under six feet, and weighing more than 1,500 pounds, the bear is built with long legs suited for chasing down prey on the plains.

You glide down to wait on the sidelines with other condors and a few coyotes. After the big predator eats its fill and saunters off, the real party begins. You share the carcass with a host of other Pleistocene scavengers: vultures, coyotes, ravens, wolves, and various rodents. You dive headfirst into the belly. In short time all that remains of the mighty bison is a scattering of gnawed bones and hair.

The sunset casts a warm pink glow over the Pleistocene plains. You soar back over mastodons still grazing, back over the rhinos, back over the torn-up earth of the bison herd, and back to your nest on a rocky outcrop. You spot the cheetah from your perch as it slinks through the grass towards the ever-wary pronghorn. The cheetah coils itself, a hairpin trigger of teeth and claws. The chase ensues. You may just get an evening snack.

Every week since 1991, Field Notes has inquired about Montana’s natural history. Field Notes are written by naturalists, students, and listeners about the puzzle-tree bark, eagle talons, woolly aphids, and giant puffballs of Western, Central and Southwestern Montana and aired weekly on Montana Public Radio.

Click here to read and listen to more Field Notes. Field Notes is available as a podcast! Subscribe on Apple Podcasts or wherever you listen to podcasts.

Interested in writing a Field Note? Contact Allison De Jong, Field Notes editor, at adejong [at] montananaturalist [dot] org or 406.327.0405.

Want to learn more about our programs as well as fun natural history facts and seasonal phenology? Sign up for our e-newsletter! You can also become a member and get discounts on our programs as well as free reciprocal admission to 300+ science centers in North America!