Camas Bulbs

by Nancy Heil

Broadcast 2.24 & 3.1.2019

Camas blooming in Packer Meadows at Lolo Pass. Photo by Allison De Jong.

Listen:

On a recent early winter morning I am cross-country skiing along the trails at Lolo Pass in the Bitterroot Mountains. As I glide along Packer Meadows in the breaking dawn, I think about early summer when this is a wet meadow awash with a sea of camas blooms.

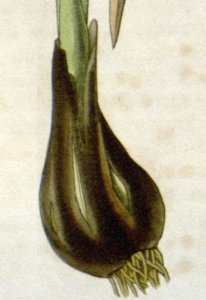

Camas bulb. Illustration from Curtis’s Botanical Magazine, public domain.

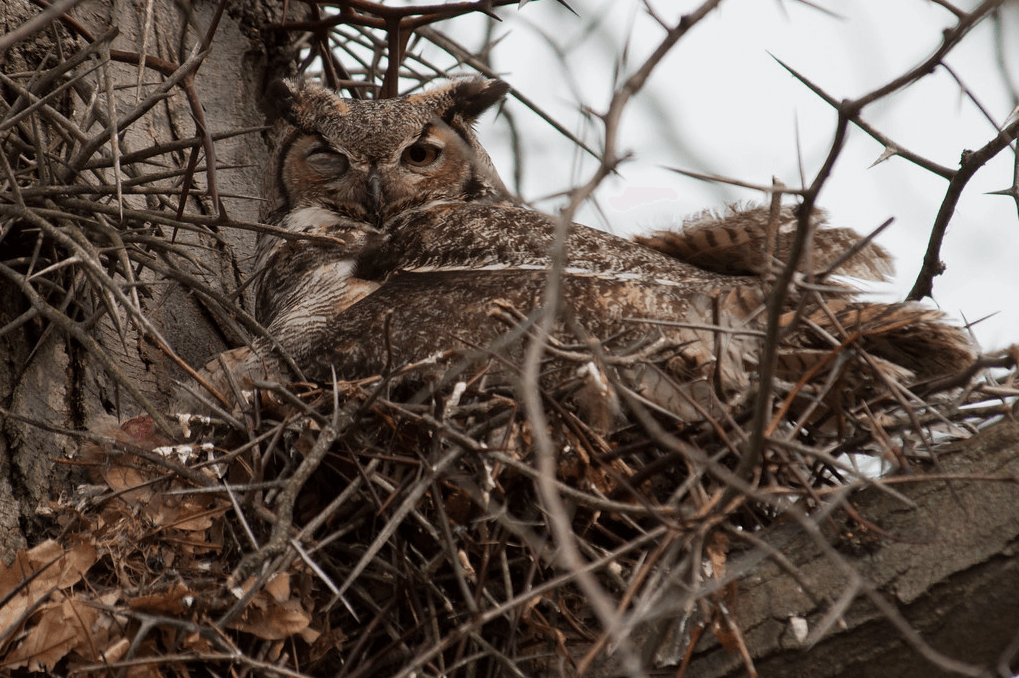

The camas, or Camassia quamash, produce blue-violet six-petaled flowers on stalks rising above the main stems. They bloom so profusely and in such numbers that they can look like a pool of water.

On this day, however, the meadow is covered with a thick blanket of snow. There is no sign of the camas. However, there is plenty going on underground. Camas is a perennial plant, formerly in the lily family and recently reclassified in the asparagus family. Like many of its relatives, camas produces an underground storage bulb to see it through the winter. A bulb is a modified underground stem that stores food. It stays dormant during the winter, then provides energy for the plant to start growing in the spring. So today, unseen by me, thousands of camas bulbs lie hidden beneath the snow, inactive for now, but with everything needed when it’s time to rise.

As I pause to adjust my layers of warm clothing, I wonder how bulbs survive the freezing temperatures. Part of the reason may have to do with insulation. It turns out that soil temperatures don’t drop nearly as low as air temperatures. The snow provides further insulating properties.

Another reason can have to do with a bulb’s chemical makeup. Some of its energy is stored in the form of complex carbohydrates. Cold temperatures can trigger a bulb’s stored starches or complex carbohydrates to break down into simpler sugars, which lower the temperature at which water freezes, much like putting salt on a sidewalk does. Perhaps some combination of factors is at work for the camas bulbs.

The complex carbohydrates and sugars that allow the plant to survive can also provide food for humans. Camas has been an important plant for indigenous peoples, including the Salish, for millennia. Camas bulbs include a complex carbohydrate called inulin, which can be very difficult to digest. After cooking, the bulb’s inulin converts to the simpler sugar fructose, making it tastier and easier to digest.

As I start moving again to stay warm, I marvel at the variety of adaptive strategies to make it through winter. Burrowing underground does have its appeal. Next time you are out a winter day, consider all that might be going on below the snow and imagine what might emerge in the spring.

Every week since 1991, Field Notes has inquired about Montana’s natural history. Field Notes are written by naturalists, students, and listeners about the puzzle-tree bark, eagle talons, woolly aphids, and giant puffballs of Western, Central and Southwestern Montana and aired weekly on Montana Public Radio.

Click here to read and listen to more Field Notes. Field Notes is available as a podcast! Subscribe on iTunes, Google Play, or wherever you listen to podcasts.

Interested in writing a Field Note? Contact Allison De Jong, Field Notes editor, at adejong [at] montananaturalist [dot] org or 406.327.0405.

Want to learn more about our programs as well as fun natural history facts and seasonal phenology? Sign up for our e-newsletter! You can also become a member and get discounts on our programs as well as free reciprocal admission to 300+ science centers in North America!