An Unexpected Visitor

by Linda Miller

Broadcast 8.3 & 8.6.2021

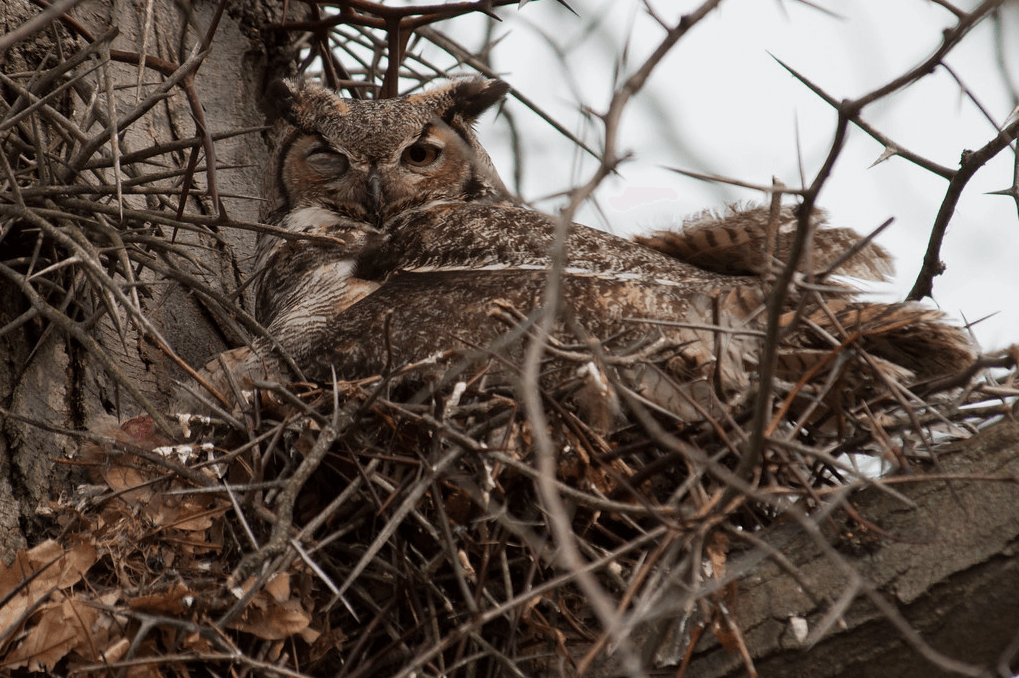

Photo by Kameron Perensovich, CC 2.0.

Listen:

Soft alpenglow lit up the Swan Mountains to the east of my home as the sun started its slow slide toward the Salish Mountains in the west. The evening shadows crept across the landscape reminding me it was time to call it a day. After I put the gardening tools into the shed for the night, I paused to watch the breathtaking sunset glow. Gratitude filled my heart.

Noisy chirps, squawks and calls of excited birds interrupted my reverie. As I made my way toward the garden area in our meadow, the raucous hubbub grew louder. Robins, Red-winged Blackbirds, Blue Jays, and Chickadees were flying in circles around my fenced garden. I searched for the reason for the commotion and to my astonishment, I saw an unexpected visitor.

What appeared to be a very large owl was perched on a corner post of the garden fence. What on earth was an owl doing in our garden? In the twenty-five years I have lived in Montana, I have never seen an owl around our place, although my husband and I have sometimes heard the hoots of Great Horned Owls and Barred Owls in the distant trees at night. This owl was about 100 feet from where I stood in the gathering dusk, so I grabbed the binoculars and a spotting scope which we always keep handy.

The binoculars revealed a silver-gray owl close to two feet in height, with patches of brownish-gray barring throughout. Its facial disc was broad with a black patch under its muted yellow beak. Just below the black patch were two horizontal white patches, which looked like a butler’s bow tie. Two whitish feather mounds created an X pattern between its eyes.

I recalled seeing a Great Gray Owl with large yellow-gold eyes in Glacier National Park which looked very similar to this visitor. I checked for yellow-gold eyes through the spotting scope to differentiate it from the smaller Barred Owl, which resembles the Great Gray but has dark eyes. Its right eye gleamed yellow-gold; but its left eye looked very shrunken, dried out and surrounded by a rusty red color. My heart sank. I realized something was seriously amiss with this Great Gray’s left eye. Was it bleeding, was he hurting? I had no idea how to help this wild creature, or whether it truly needed any help at all.

A few deep breaths later, relief washed over me as I watched this incredible owl quietly survey our garden and vole-filled meadow, without any obvious signs of pain, agitation or confusion. Great Gray Owls’ eyes are in a fixed position in their skull for stability, allowing only a two degree range of movement. Instead of moving their eyes to scan the environment, they have the ability to rotate their head a full 270 degrees. This owl had no difficulty rotating its head, although it consistently rotated it toward the left more frequently than to the right (where I stood), as if to compensate for a blind spot on its left side. It had clearly experienced some type of injury or possibly disease which had impaired its left eye, but the eye did not appear to be currently bleeding. Our Great Gray also did not look thin or disheveled which can indicate malnourishment and difficulty with hunting.

Since meeting our garden visitor, I have learned that most species of owls who have the functional use of only one eye can still hunt successfully and thrive, almost as well as a full-sighted owl, so long as they have intact hearing. The Great Gray is a nocturnal hunter and relies primarily on its hearing for a productive hunt. Its ears are positioned asymmetrically on each side of its head, giving it asynchronous ear canals. This allows the owl to triangulate the exact location of its prey very accurately, even without full vision.

After approximately twenty enchanting minutes, my new buddy lifted off the garden perch with effortless grace. It flew in a southward direction over the meadows without any discernible sounds or difficulties while gaining elevation. I watched it through binoculars as it deftly maneuvered its way through the tall ponderosa pine and Douglas-fir trees to disappear into the distant forest. What an inspiring gift!

Every week since 1991, Field Notes has inquired about Montana’s natural history. Field Notes are written by naturalists, students, and listeners about the puzzle-tree bark, eagle talons, woolly aphids, and giant puffballs of Western, Central and Southwestern Montana and aired weekly on Montana Public Radio.

Click here to read and listen to more Field Notes. Field Notes is available as a podcast! Subscribe on iTunes, Google Play, or wherever you listen to podcasts.

Interested in writing a Field Note? Contact Allison De Jong, Field Notes editor, at adejong [at] montananaturalist [dot] org or 406.327.0405.

Want to learn more about our programs as well as fun natural history facts and seasonal phenology? Sign up for our e-newsletter! You can also become a member and get discounts on our programs as well as free reciprocal admission to 300+ science centers in North America!