Water-Loving Willows

by Lena Viall

Broadcast 10.11 and 10.16.2015

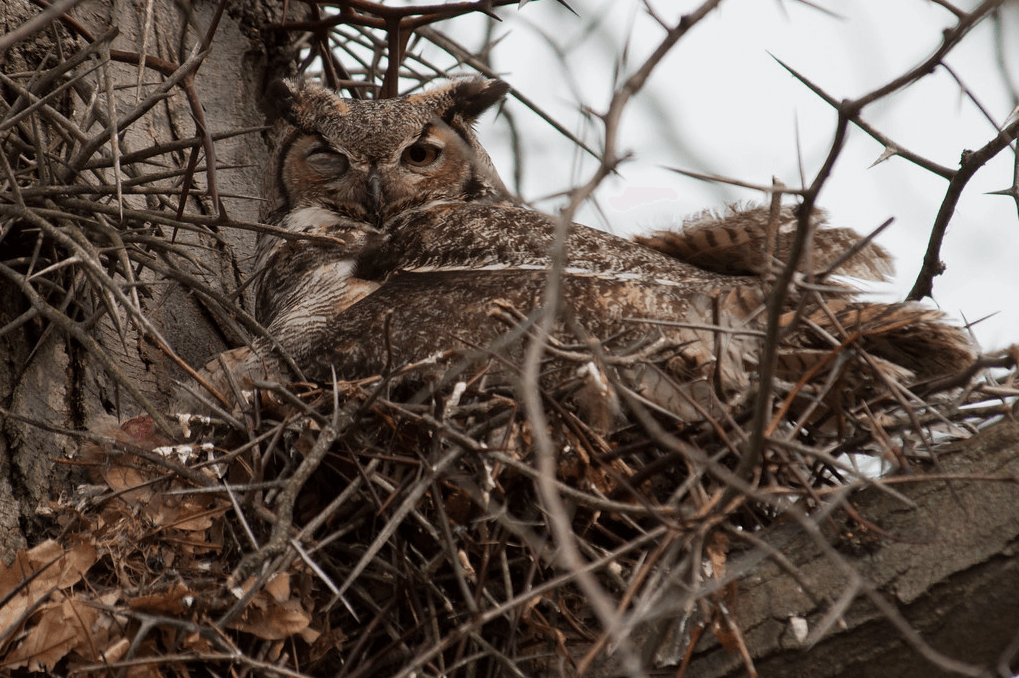

Photo by Flickr user Jon Hurd (CC 2.0).

Listen:

Amidst the rugged gumbo-ridge landscape of more easterly Montana, water is everything. With hotter summers than the western half of our state, and with drier winters, the Montana of my childhood does not have the many deep, clear, blue lakes that look up from the covers of most Montana travel brochures. It is the small, isolated watering holes dotting the prairies that sustain life here.

Yet a sharp eye only need scan the horizon for the outline of a deciduous tree to pick out a probable spring. There might not be another tree for miles around, and yet, like an X on a pirate map, a willow or its cousin seems to have marked every lonely, mossy pond. They seem to shout to the thirsty explorer, “Here! Here is water!” But how did the willows come to populate and perpetuate in locales so remote?

The Salicaceae family, which includes willows as well as poplars, aspens and cottonwoods, is one of determined opportunists. Salicaceae is one of the most widespread of tree families, taking root on every continent but Antarctica and all across the United States. Quick-growing and quick-dying, these trees provide shelter and reliable food sources for birds, insects and mammals of all sizes. To a hungry elk, nothing hits the spot quick like a snack of new Salicaceae shoots. And true to observation, members of the Salicaceae family are generally found near sources of water.

In their own Salix genus, willows specifically have long been used by humans the world over. Their flexible branches have been woven into everything from utilitarian baskets to religious ceremonies. Ancient peoples used the salicin found in willow bark as pain reliever long before we learned to synthesize aspirin from it. But nowhere are willows as diverse and prolific as here in North America.

There are dozens of species of Salix in the Northwest alone. From the tall, yawning peachtree willow of my childhood shelterbelt to the thin, shrubby sandbar willow lining our rivers and streams, willows come in many forms. Oftentimes, they will hybridize between species, making identification notoriously tricky even to the most seasoned naturalist. But from 50 feet high down to five, it is their virility that is the secret to the willows’ success.

Montana’s willows form their catkins – rod-shaped flowers, petal-less and about two inches long – in mid-spring. The insect-pollinated catkins will spend the month of May developing into seeds. Then, just as the annual spring snow runoff peaks, the willows release their seeds in an explosion of fluff. Attached to gossamer-like threads that naturally catch the wind (the “cotton” of cottonwoods), the miniscule seeds lift off into the surrounding landscape and rain down around the parent tree and into the nearby water. Yet, for all their aviation abilities, the seeds often fall within a fairly small area, usually within 250 yards of the parent plant.

Photo by Edward Johnson (CC 3.0).

However, the willows have things perfectly timed: with the runoff now subsiding, the willow seeds have the best chance of finding wet, newly-flooded soil to thrive in. Of course, a few lucky seeds will be carried to the next valley over by a strong breeze or river current, to take root somewhere entirely new. That is how, initially, all willows at remote watering holes must start. But the majority of seeds will land close to home, where the going is already good.

Once on the ground, willow seeds are astonishingly fertile. In many species, upward of 95 percent of all seeds will germinate given the right conditions. But in addition to their prolific seeds, many members of the Salicaceae family also sucker, sending up new shoots directly from the parent’s roots. It’s not surprising, then, that the determined willow would quickly spread across a continent, line an entire length of riverbank – or that one would come to stand sentinel over the same lonely prairie pond for generations.

Every week since 1991, Field Notes has inquired about Montana’s natural history. Field Notes are written by naturalists, students, and listeners about the puzzle-tree bark, eagle talons, woolly aphids, and giant puffballs of Western, Central and Southwestern Montana and aired weekly on Montana Public Radio.

Click here to read and listen to more Field Notes. Field Notes is available as a podcast! Subscribe on iTunes, Google Play, or wherever you listen to podcasts.

Interested in writing a Field Note? Contact Allison De Jong, Field Notes editor, at adejong [at] montananaturalist [dot] org or 406.327.0405.

Want to learn more about our programs as well as fun natural history facts and seasonal phenology? Sign up for our e-newsletter! You can also become a member and get discounts on our programs as well as free reciprocal admission to 300+ science centers in North America!