Text and photos by Allison De Jong

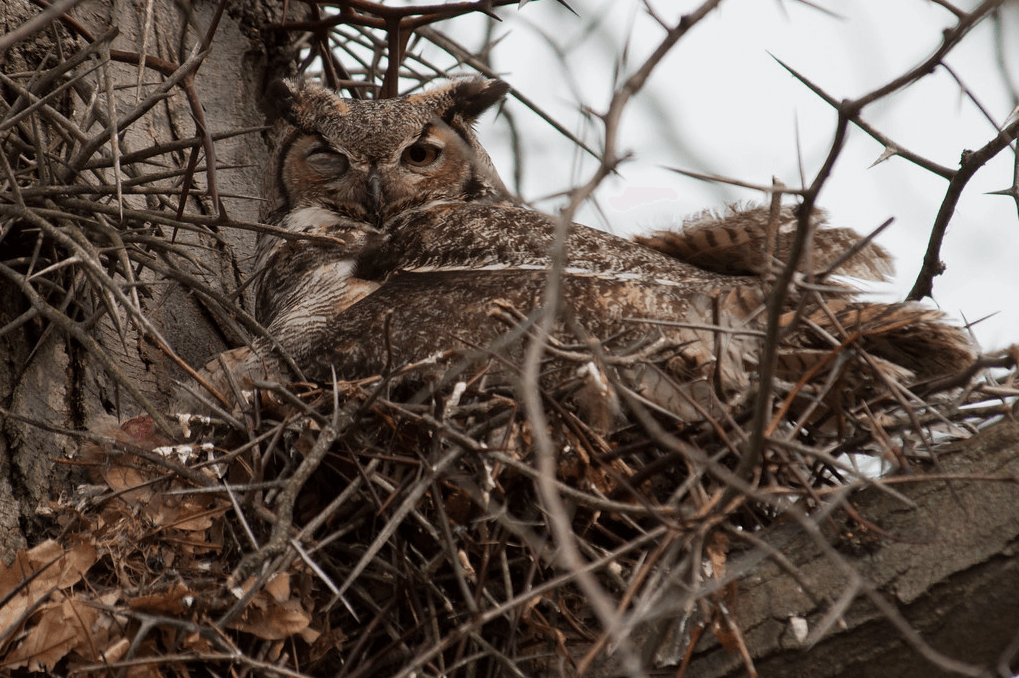

It was a sunny, gorgeous Sunday in late July. My husband, two friends and I had scattered ourselves across the broad alpine meadow of Goat Flat in the Anaconda-Pintler Wilderness, noses to the ground, peering at the myriad tiny wildflowers strewn across the landscape; most of the bright bits of color reached no higher than the top of our hiking boots. From a distance the meadow looked fairly uniform—low, matted plants, flashes of intermingled colors—but upon closer inspection, the flowers revealed dozens of unique shapes and shades.

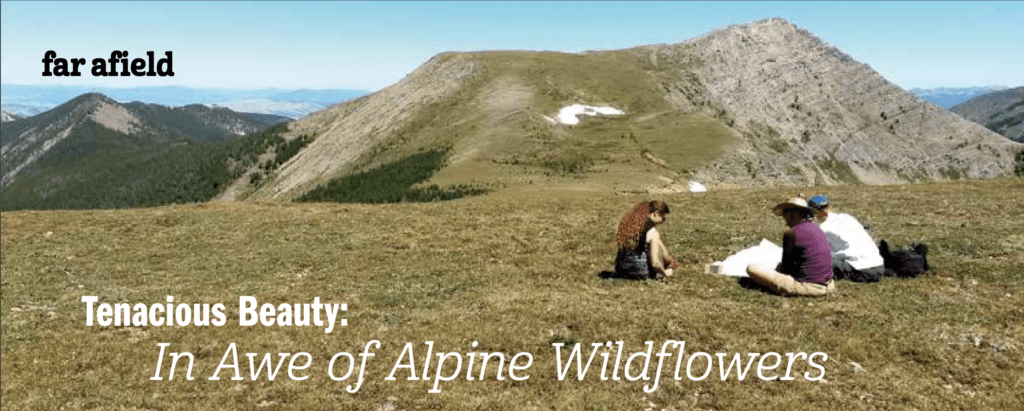

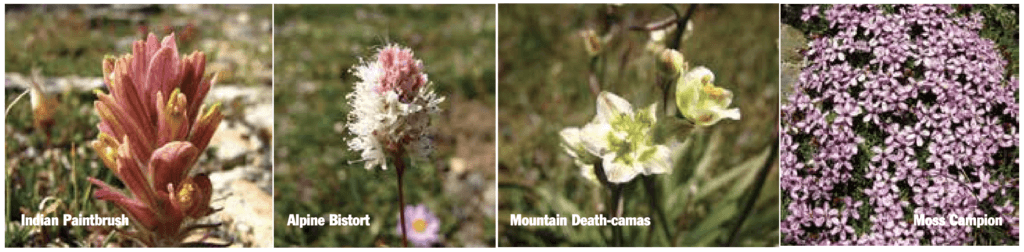

Paintbrush, their colorful bracts low to the ground, painted a vivid magenta. A plant with a tall reddish stem and a spiraling cluster of white flowers on top: alpine bistort (Bistorta vivipara), which I’d never seen before. Another white flower, six-petaled, with a circle of green on the inside: mountain death-camas (Zigadenus elegans), so toxic that the Okanagan people mashed up the bulb and used its poison to tip their arrows.

The tundra is a harsh environment, and the species that live there have, through necessity, adapted to be tough little buggers. Their home is scoured by wind, subject to bitter temperatures (on both extremes), and exposed to intense solar radiation. Not only that, it’s covered with snow eight to nine months out of the year, making for a very short growing season; even during the summer months frost can descend at any time. Yet these little plants make do and even thrive. And when I knelt down for a closer look, I was reminded that toughness in no way precludes beauty—up close, these tiny flowers were vivid and breathtaking.

Crouched down, I also realized that there was a difference between the conditions at human level and the conditions at alpine wildflower level. The breeze I felt standing up was greatly diminished near the ground. The sunshine beat down. The ground was warm, its heated surface sending up an earthy fragrance. I could understand why the plants here had adapted to be shorter than their lower-altitude counterparts—in this environment, a few inches is the difference between survival and extinction.

Alpine plants have other adaptations as well. In a windy environment, wind-dispersed seeds are an advantage, so many tundra plants have seeds that are winged, or hairy, or tiny and lightweight. Another form of wind dispersal is found in plants like paintbrushes, campions, and poppies, which have capsules on stems that stick up through the crust of the first early snowfall: when buffeted by the wind, they drop their seeds atop the crusty snow to be skittered away across the landscape. The leaves of some alpine plants, such as louseworts, some saxifrages, and Sitka valerian (Valeriana sitchensis), have deep red and purple pigmentation to warm themselves more quickly when the sun comes out, and the dark colors may also help protect the plants from the sun during their more sensitive phases in spring and fall. Another common adaptation is hairiness, which can provide protection from the sun, keep moisture from escaping, and even create a greenhouse effect by holding in heat and warming the plant.

Goat Flat is home to many of these plants. That bright July day, we continued to amble across the hummocky landscape, moving slowly, not wanting to crush any of the minute flowers beneath our boots. Grasses intermingled with the flowers which intermingled with cushiony mosses, patches of bare earth, and scattered rocks. A sprinkling of low white flowers caught my eye, and I bent down for a closer look. The flowers were cup-shaped with dark bluish-purple dots on the edges of the petals and a few vertical stripes of the same deep hue tinting the outside of the “cup.” My plant-loving husband told me it was a gentian—I’d never seen a white gentian before—and I found out later from my field guide that it was the aptly-named whitish gentian (Gentiana algida). The field guide also informed me that one of this plant’s adaptations is to close up its petals before storms, presumably to keep its pollen from being swept away by the rain.

Another gentian in this meadow was impossible to miss: monument plant (Frasera speciosa). It was one of the few flowering plants that stood taller than a hiking boot; in fact, it was about two feet tall and looked rather like a Christmas tree, the bottom half whorls of lance-shaped leaves; the top half mostly greenish-white flowers with deep purple flecks. And, of course, this plant also has some impressive adaptations: the plant populations form their flowers three years or more before they actually bloom, and then the plants all flower together . . . and then die. The leaf litter from the parent plants helps protect the seeds and new young plants as they grow and start the process all over again.

Approximate scale of alpine wildflowers. Illustrations contributed by the Missouri Botanical Garden, U.S.A. and the U.S. Geological Survey Library, U.S.A.

The more I ponder the array of alpine plant adaptations, the more I wonder if my perception of the tundra as harsh is completely accurate. It is harsh to me—I could not survive there. But if I were a plant like a mountain avens (Dryas sp.), with bowl-shaped flowers that reflect and focus sunlight to speed up growth as well as provide a warm, enticing spot for pollinators to land, perhaps I would not perceive a meadow at 9,500 feet above sea level as such a challenging place. After all, the deep snows found in some alpine areas insulate the ground—and the dormant plants—below, and may provide such protection for nearly nine months of the year. Indeed, Goat Flat still had a few lingering snow fields melting away in the last week of July.

Visiting this remote, wild place reminded me that my human perspective is limited. To the flowers that bloom there, I am just a shadow that falls across their petals or a shoe that crushes. I am but a brief visitor in a cycle of sun and cold and wind that has spanned millennia.

What might future years bring to alpine habitats such as this? Our too-rapidly-changing climate threatens the survival of the flora and fauna that make their homes in high-altitude places like Goat Flat. Yet I can’t help but find hope in the fact that the vast array of plants in that meadow have developed myriad creative adaptations to conditions we humans consider harsh. I am humbled by their resiliency, and I can’t help but believe that they will continue to adapt, somehow, to whatever comes next. And I find in myself a renewed desire to protect their habitats, so that these wild places, and the plants that call them home, will remain to awe future naturalists with their exquisite perseverance.

Allison De Jong is editor of Montana Naturalist magazine and MNHC’s Field Notes on Montana Public Radio. She loves all things natural history, but flowers most of all.

This article was originally published in the Fall 2014 issue of Montana Naturalist magazine, and may not be reproduced in part or in whole without the written consent of the Montana Natural History Center. ©2014 The Montana Natural History Center.

Click here to read more articles from Montana Naturalist magazine.

Want to learn more about our programs? Sign up for our e-newsletter! You can also become a member and get discounts on our programs as well as free reciprocal admission to 300+ science centers in North America!