Butterflies in Winter

Broadcast 3.10 & 3.15.2019

by Brett Walker

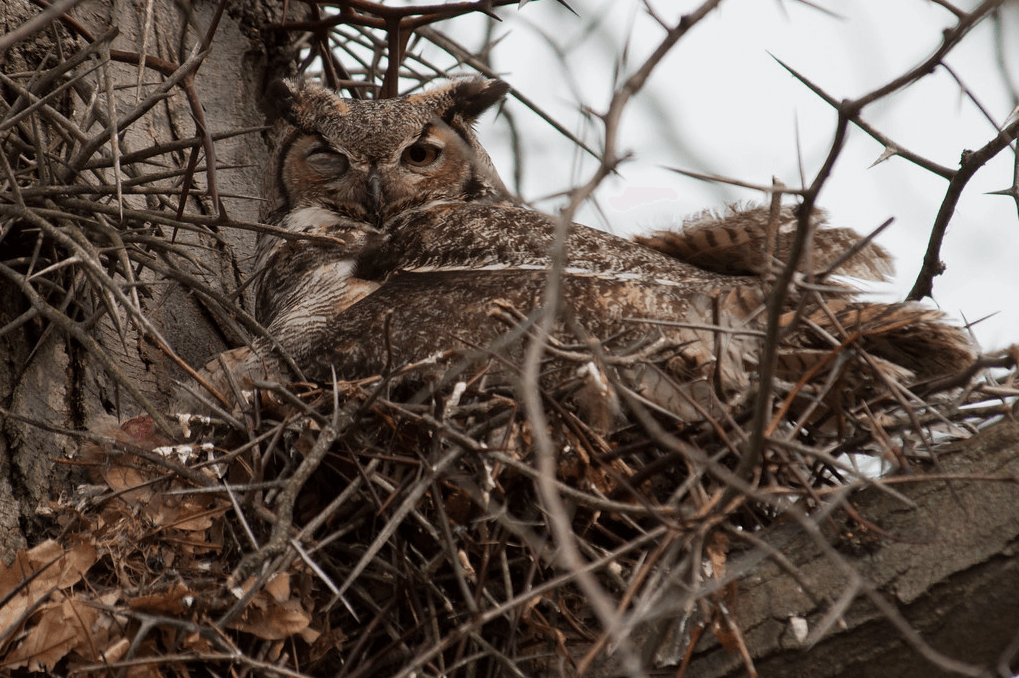

A comma butterfly (Polygonia sp.) hibernating in winter. Photo by Harald Süpfle, CC 2.0.

Listen:

Here’s a topic you might not be thinking much about right now. Remember all those colorful butterflies that visited your garden just a few short months ago? They seemed the very definition of summer. What’s happened to those delicate creatures?

Among the approximately 700 species of North American butterflies there are three main strategies that have evolved for winter survival. The first involves diapause, either as an egg, a caterpillar, or in a protective pouch called a chrysalis. Hibernation in the adult form is the second strategy. The third and final solution is simply to head south.

Most butterflies we see in western Montana spend the winter months right here in a condition called diapause. During diapause in any life stage, butterflies will not grow, develop, or reproduce. Butterflies usually start their diapause in late summer or early fall as the days get shorter and temperatures drop. But some species at this latitude, like the Yellowstone checkerspot, may start as early as July.

Like other insects, each generation in a butterfly’s life cycle starts with an egg laid on or near a host plant by an adult female. The egg hatches into a caterpillar which in turn grows and eventually encases itself within a chrysalis. Inside this chrysalis the caterpillar transforms itself, then emerges to fly away.

Many species of butterfly spend their winter diapause in one of these first three life stages. Eggs and caterpillars can be found in protected areas on or near the host plants that they use for food in the spring. Other butterflies, like those in the well-known swallowtail family, winter in the chrysalis stage securely attached within dense vegetation.

Those butterfly species hardy enough to survive the harsh winters by hibernating as adults, such as the Milbert’s tortoiseshell, are few and far between. Those that do, winter in secluded nooks and crannies, sometimes in small single-species groups.

In addition to hiding in protected areas all wintering life stages also have special adaptations for survival. Just like Montana drivers who add antifreeze to their car radiators, butterflies prevent damage to their insides by increasing the level of glycerol, a type of alcohol in their blood, and by converting excess water in their bodies into a gelatin-like substance that won’t freeze.

Finally, like many of the migratory songbirds, a substantial number of butterflies migrate to more favorable southern climes in the winter. In a spectacular fall migration individual painted lady butterflies can cover more than 1,200 miles on the way to their wintering grounds in the southwest United States and Mexico. Northward migration in the spring, however, can take several generations to complete. Returning adults stop traveling to lay eggs on host plants. When their offspring emerge, they too move north like their parents. This means that the painted ladies returning to Montana in the summer may be several generations removed from the ones that headed south the previous fall.

Until spring when longer days and warmer temperatures bring butterflies out of winter diapause, it’s easy to forget about them. So the next time you head out on a winter hike, you may be lucky enough to discover the tiny eggs of a willow hairstreak on the underside of a stem, a Lorquin’s admiral caterpillar in a rolled leaf, or maybe even a hibernating green comma.

The animal world is still alive in winter. But some members, like the butterflies, are just waiting for another spring.

Every week since 1991, Field Notes has inquired about Montana’s natural history. Field Notes are written by naturalists, students, and listeners about the puzzle-tree bark, eagle talons, woolly aphids, and giant puffballs of Western, Central and Southwestern Montana and aired weekly on Montana Public Radio.

Click here to read and listen to more Field Notes. Field Notes is available as a podcast! Subscribe on iTunes, Google Play, or wherever you listen to podcasts.

Interested in writing a Field Note? Contact Allison De Jong, Field Notes editor, at adejong [at] montananaturalist [dot] org or 406.327.0405.

Want to learn more about our programs as well as fun natural history facts and seasonal phenology? Sign up for our e-newsletter! You can also become a member and get discounts on our programs as well as free reciprocal admission to 300+ science centers in North America!