Story by Hank Fischer

Story by Hank Fischer

Photos by Carol Fischer

Henry David Thoreau once wrote, “He who hears the rippling of rivers will never despair of anything.”

Certainly the whispering waters of Montana’s Smith River have that magical ability to soothe one’s soul. The sixty-mile float from Camp Baker to Eden Bridge may well be Montana’s premier river trip. While the Smith is well known for its fabulous trout fishing and incredible scenery, many people don’t realize what a remarkable river it is for watching birds.

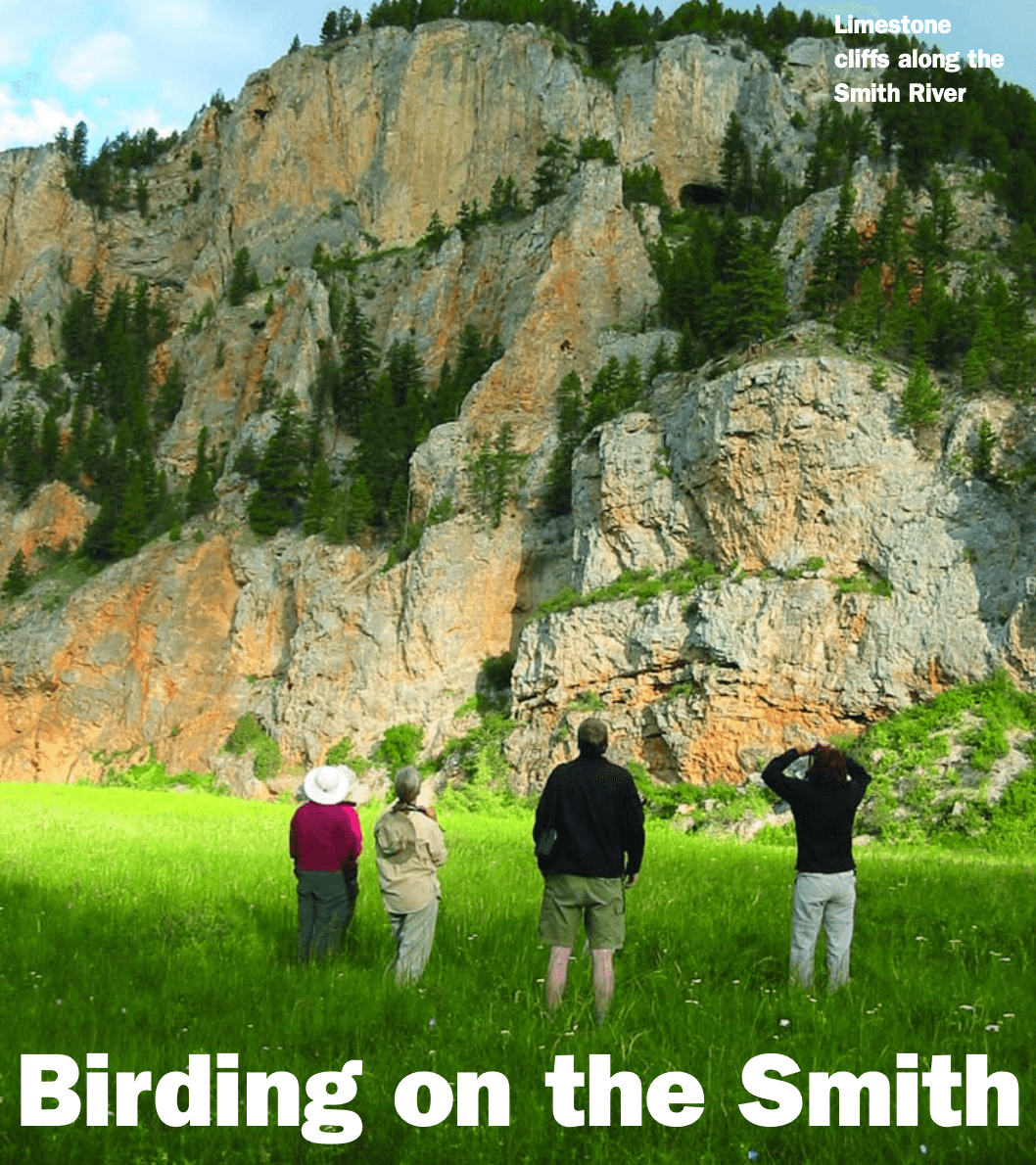

What makes it exceptional is its mixture of habitats. Tall cottonwoods and dense willow thickets thrive along the stream, and they support a diversity of songbirds, including flycatchers, goldfinches, bluebirds, and warblers. The river itself provides sustenance for another host of birds, such as waterfowl, pelicans, herons, dippers, and kingfishers. But what is truly unique about the Smith are the limestone cliffs that tower for hundreds of feet over the river. These cliffs not only provide homes for small birds like swallows and swifts, they also provide nesting and hunting grounds for birds of prey, including Prairie Falcons, Peregrine Falcons, and Golden Eagles.

On a June 2004 Smith River trip, our group of 12 people (most with average bird knowledge except for our ringer, University of Montana ornithology professor Dick Hutto) spotted 82 species of birds on a four-day trip. One of the best sightings occurred at the spectacular and appropriately named Sunset Cliffs, which rise straight up from the river for nearly a thousand feet in brilliant rose and tan glory. From our camp we watched a family of Prairie Falcons—two adults and two young—on a nest among the rock spires. They were visible throughout the evening and the next morning, the adult falcons frequently chasing White-throated Swifts to feed to their young.

On a June 2004 Smith River trip, our group of 12 people (most with average bird knowledge except for our ringer, University of Montana ornithology professor Dick Hutto) spotted 82 species of birds on a four-day trip. One of the best sightings occurred at the spectacular and appropriately named Sunset Cliffs, which rise straight up from the river for nearly a thousand feet in brilliant rose and tan glory. From our camp we watched a family of Prairie Falcons—two adults and two young—on a nest among the rock spires. They were visible throughout the evening and the next morning, the adult falcons frequently chasing White-throated Swifts to feed to their young.

The White-throated Swifts are a special Smith River avian delight. These cliff-nesting birds, which frequently are mistaken for swallows, perform a feat that few birds attempt: they mate in the air! On several occasions we observed swifts as they joined together in mid-flight, fluttering and gyrating toward the ground for hundreds of feet on their way to apparent oblivion, only to separate just before reaching the earth.

Many small songbirds travel thousands of miles to reach their summer home on the Smith River. These so-called neo-tropical migrants (including warblers, vireos, tanagers, and flycatchers) spend approximately eight months of the year wintering in Central and South America and the remaining months in their breeding grounds in North America. Currently, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service classifies 11 of the 96 neo-tropical songbird species (12%) as endangered, threatened, or being of management concern, and another 65 species (68%) as showing measurable population declines.

So it was of special interest when Dick Hutto, a licensed bird bander, set up a mist net to capture songbirds in order to band them and get a better idea of migration patterns. His primary target was a Lazuli Bunting that he’d spotted on top of a nearby pine tree. This is a small bird with a brilliant blue head (named for the gemstone) and a spectacular orange breast. Dick set up an almost invisible net (about badminton size) near a small thicket and then brought out his secret weapon: an MP3 player with recorded bird calls. He dialed up the Lazuli Bunting call and as soon as its notes were heard the male bunting zoomed down like a prizefighter answering the bell for round one. It was easier than decoying a duck!

So it was of special interest when Dick Hutto, a licensed bird bander, set up a mist net to capture songbirds in order to band them and get a better idea of migration patterns. His primary target was a Lazuli Bunting that he’d spotted on top of a nearby pine tree. This is a small bird with a brilliant blue head (named for the gemstone) and a spectacular orange breast. Dick set up an almost invisible net (about badminton size) near a small thicket and then brought out his secret weapon: an MP3 player with recorded bird calls. He dialed up the Lazuli Bunting call and as soon as its notes were heard the male bunting zoomed down like a prizefighter answering the bell for round one. It was easier than decoying a duck!

To the disappointment of our breathless birdwatchers, the diminutive bird flew right over the net. Undaunted, Dick called again and the little flash of electric blue buzzed right into the trap. When released, the bunting flew back to the top of the conifer where we originally had spotted him.

So if you are floating the Smith River, try keeping track of the different kinds of birds you see or hear. Given the Smith’s alluring qualities, it’s not surprising that it’s so popular. To protect and maintain its natural qualities, Montana’s Department of Fish, Wildlife and Parks manages the stream under a permit system. If you forget to apply for a permit, you can contact the FWP office in Great Falls to check for cancellations.

Hank Fischer is co-author of Paddling Montana, a book about floating Montana rivers. He is also a conservationist, journalist, and guide, and has been extensively involved in endangered species restoration in the northern Rockies.

Ten Common Smith River Birds

Turkey Vulture. This dark bird is nearly as large as an eagle. Look for its red head. When it flies it rocks and tilts on the air currents.

Spotted Sandpiper. This is a robin-size bird, olive-brown on top with black spots on its white breast. Look for it teetering up and down along the side of the river.

Belted Kingfisher. This blue-gray bird with a stout bill can be seen perching near the river or hovering in the air before diving on a minnow. Its call is a high, loud rattle.

White-throated Swift. This black-and-white bird can be distinguished from a swallow by its narrow, stiff wings that appear to bend only at the shoulder. They congregate in large groups near cliff walls.

Common Nighthawk. Distinguished by its long, pointed wings and notched tail. Usually flies at dusk; its wings have a white bar.

American Dipper. This slate-gray bird with a stubby tail can be seen bouncing up and down next to the stream or swimming underwater in search of insects. Also known as a Water Ouzel.

Gray Catbird. This robin-sized bird is all gray with a black cap. It gets its name from its mewing call. Usually seen on the ground in underbrush.

Common Yellowthroat. This small warbler is olive green above and bright yellow below. The males have a black face mask. Often seen near the edges of thickets.

Lazuli Bunting. This small member of the finch family has a turquoise blue head with a cinnamon breast and sides. Often seen near the edge of thickets or perched on the top of a pine tree.

Prairie Falcon. Pointed wings and long tail, sandy brown in coloration. You can distinguish it from a Peregrine Falcon by its black armpits. Look for nests on the cliff walls or listen for its kree-kree-kree call.

This article was originally published in the Spring/Summer 2006 issue of Montana Naturalist magazine, and may not be reproduced in part or in whole without the written consent of the Montana Natural History Center. ©2006 The Montana Natural History Center.

Click here to read more articles from Montana Naturalist magazine.

Want to learn more about our programs? Sign up for our e-newsletter! You can also become a member and get discounts on our programs as well as free reciprocal admission to 300+ science centers in North America!