by Allison De Jong

The first time I heard a pika, I was hiking along a talus slope on the Bass Creek trail in the Bitterroot Mountains. I would have imagined the short, shrill sound to be some kind of bird call were it not for my husband’s excited whisper—“Listen. That’s a pika!” Following his pointing finger, my eyes fell upon a small grey ball of fur that was nearly camouflaged among the surrounding rocks, and, as I watched, it darted out of sight beneath the tumbled scree.

Pika photo by April Craighead. Haystack photo by Lara Oles, Bridger Teton National Forest, USFS.

Since then, I have heard pikas several times while out hiking, though I’ve only been quick enough to catch a glimpse of this smallest member of the rabbit order on one other occasion. While not always easy to spot in the wild, in the past few years pikas have come increasingly into the public eye due to their decreasing population and studies linking this decline to the changing climate.

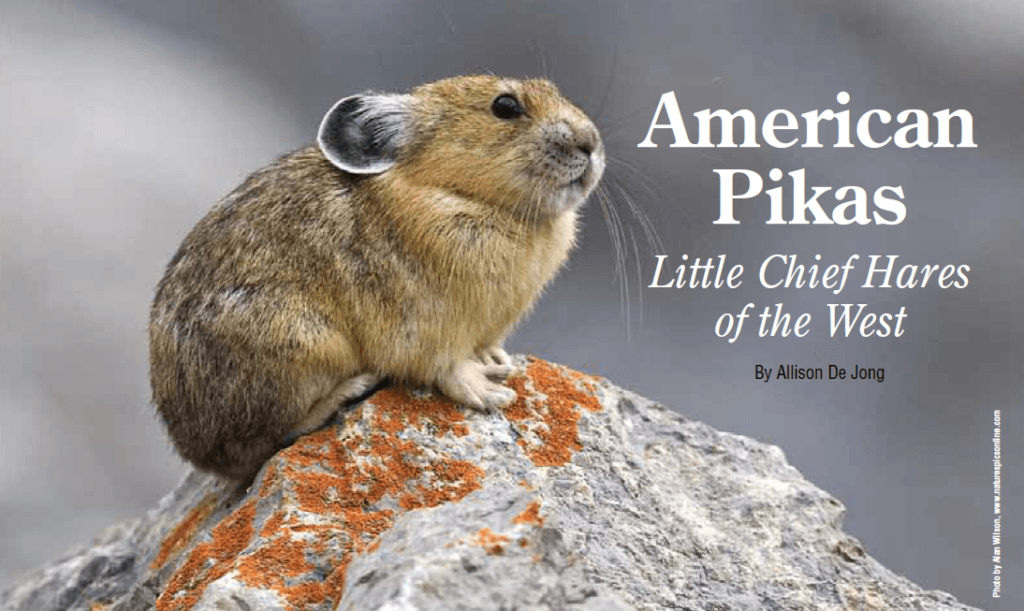

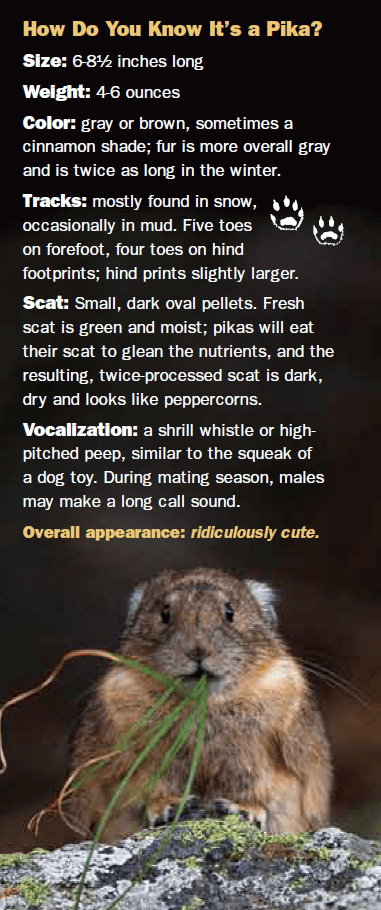

The American pika (Ochotona princeps), also called “rock rabbit” or “little chief hare,” is one of 30 species of pika worldwide, and lives on talus slopes in alpine ecosystems from California and New Mexico north to Alberta and British Columbia. While in the northernmost reaches of their range they may be found at relatively low elevations, they generally live between 6,000 and 13,000 feet above sea level. Pikas are about the size of a potato, and at first glance rather resemble one with their grayish-brown coloring and lack of a visible tail. Up close, an observer will notice the pika’s round ears, whiskered nose, and tiny paws—and, in many cases, its mouth full of grasses and other plants, which it tirelessly harvests in the summer and early fall.

The talus slopes and rocky areas that pikas call home are generally near meadows, from which they collect plant material to sun-dry and form into haystacks to supplement their winter diet. Unlike many mountain animals, pikas neither migrate nor hibernate, and must therefore store enough food to get them through a winter of wakefulness. Their dense fur helps them survive the cold temperatures, as does spending most of the time in dens and tunnels in the protected subnivean (“under the snow”) layer. Sometimes their harvested stores don’t last through the winter, and pikas must then forage on lichens and cushion plants under the snow until spring melt.

Pikas breed in the late spring, usually in May or June, and will sometimes have a second litter in July or August. Litters consist of two to six young, which grow quickly, reaching their adult size in about three months, though they do not reach sexual maturity for about a year. Pikas may live as long as seven years, but most live for only three or four, largely because of predation by eagles, hawks, owls, weasels, coyotes, foxes and bobcats.

Photo by Don Getty, DonGettyWildlifePhotograpy.com.

Life in a Stressful Climate

Aside from the usual challenges of survival, pikas are now faced with an increasingly pervasive threat: the changing climate. This past July, April Craighead, a wildlife biologist from the Craighead Institute in Bozeman, spent an afternoon at the Montana Natural History Center leading a training for citizen scientist volunteers interested in helping with a statewide pika survey. We learned that pikas, because of their thick fur and high core body temperature, are extremely sensitive to heat. If unable to find shelter in a cool place, they can overheat and die in as little as six hours if exposed to temperatures above 80 degrees Fahrenheit.

According to Craighead, because they are sensitive to even small changes in temperature and occupy such a narrow ecological niche, pikas are an ideal indicator species for climate change and its environmental and biological effects. Several studies on pika populations and habitat have been conducted in recent years, with a clear connection emerging between warming temperatures and decreasing pika populations.

With their need to live in high, cool, rocky habitats, pikas are essentially island dwellers. They live in alpine areas; they do not migrate; they do not travel long distances—some spend their entire lives within a half-mile radius—and thus they largely remain in isolated pockets of suitable environments scattered across the West. When average summer temperatures go up, pikas have no choice but to move up the mountainsides, much as a creature living on an island must move to higher ground when water levels rise. Eventually, if temperatures rise high enough, pikas will have nowhere to go.

Ironically, the changing weather patterns mean that not only do pikas run a higher risk of overheating in the summer but also of freezing in the winter. Pikas depend upon an adequate snow layer to protect them from frigid temperatures; without the relative warmth of the subnivean layer, they may die from overexposure. More intense freezing and thawing patterns can also be detrimental to pikas’ tunnels beneath the snow, causing them to collapse and making it difficult for pikas to access their winter food stores.

The goal of the Craighead Institute’s pika survey is to provide accurate locations for pika populations throughout the state. Craighead informed us that, though pikas are widespread across Montana, we have very little information on where they actually live. As more and more citizen scientists share in the effort to record pika locations, the increased amount of data will help wildlife professionals and agency personnel to identify populations threatened by climate change as well as areas that may provide refuge in the future.

Little did I know, when we saw that pika scampering on a rocky slope in the Bitterroot Mountains, that this little species faces such significant challenges to its survival. There doesn’t seem to be an easy answer for the genus Ochotona. These hardy (and undeniably cute) “little chief hares” have thrived for millennia in what we would consider to be less-than-hospitable environments. Will they be able to survive the additional hardships of rising temperatures, unpredictable weather patterns, and the ever-diminishing range of their habitat? Only time will tell.

Allison De Jong enjoys honing her writing and naturalist skills as Communications Coordinator and Montana Naturalist editor at the Montana Natural History Center. She has an M.S. in Environmental Writing from the University of Montana.

The Craighead Institute is always looking for new citizen science volunteers to assist with their Montana Pika Survey. In 2010, four citizen scientists provided data for five new pika locations. By 2015, that number had risen to 372 new pika locations, thanks to the time, energy, and passion of dedicated volunteers. Interested in helping out? Check out craigheadresearch.org/pika.html for more information or contact April Craighead at april [at] craigheadinstitute [dot] org.

This article was originally published in the Winter 2011-2012 issue of Montana Naturalist magazine, and may not be reproduced in part or in whole without the written consent of the Montana Natural History Center. ©2011 The Montana Natural History Center.

Click here to read more articles from Montana Naturalist magazine.

Want to learn more about our programs? Sign up for our e-newsletter! You can also become a member and get discounts on our programs as well as free reciprocal admission to 300+ science centers in North America!