Terrible Twins

by Wenfei Tong

Broadcast 5.14 and 5.19.2017

Listen:

The Montana spring is full of sudden new life, partly because it is so short relative to the more relaxed breeding seasons closer to the tropics. Young ungulates, or hoofed mammals, can be especially taking at this time of year, because of their gangling legs and almost instant precocity when it comes to escaping predation.

Regardless of whether they are predators or prey, most mammalian mothers invest a lot in their offspring. Take pronghorn mothers, who almost always have twins, and arguably invest more in gestation than any other North American ungulate. Pronghorn twins make up almost one fifth of their mother’s body weight at birth. To put that in perspective, mule deer, which are about a third larger, have fawns that weigh the same or less than new-born pronghorn. Meanwhile, human twins weigh less than ten per cent of a 150-pound mother.

On the surface, investing so much into growing children in the relative safety of a womb makes sense. Each child constitutes a genetic investment. It is in a mother’s evolutionary interest to have healthy children that survive to have lots of children of their own. This common interest between mothers and their children explains the famously strong protective drive that causes some female bison or bears to attack any perceived threats to their offspring.

The twist is that what’s best for mum (in terms of maximizing her lifetime investment), is not identical to what’s best for each of her individual offspring (who has more of a genetic stake in its own existence than in that of its siblings). As a result, one often sees evidence of conflict beneath the seemingly-serene surface of animal families, from squabbling siblings who aren’t keen on sharing a coveted delicacy, to mares and cows having to repeatedly reject their weaned offspring pestering for free refills at the maternal milk bar.

One aspect of biology that has long fascinated me is how natural selection has optimized maternal investments in terms of the quantity and quality of offspring a mother can have with each breeding attempt and over the course of her entire life. To maximize her lifetime reproductive success, it is in a mother’s evolutionary interests to have her current and future children share, whereas from the viewpoint of any individual child, there is a net benefit to hogging a little more than its fair share of mum’s care and attention at the expense of its siblings.

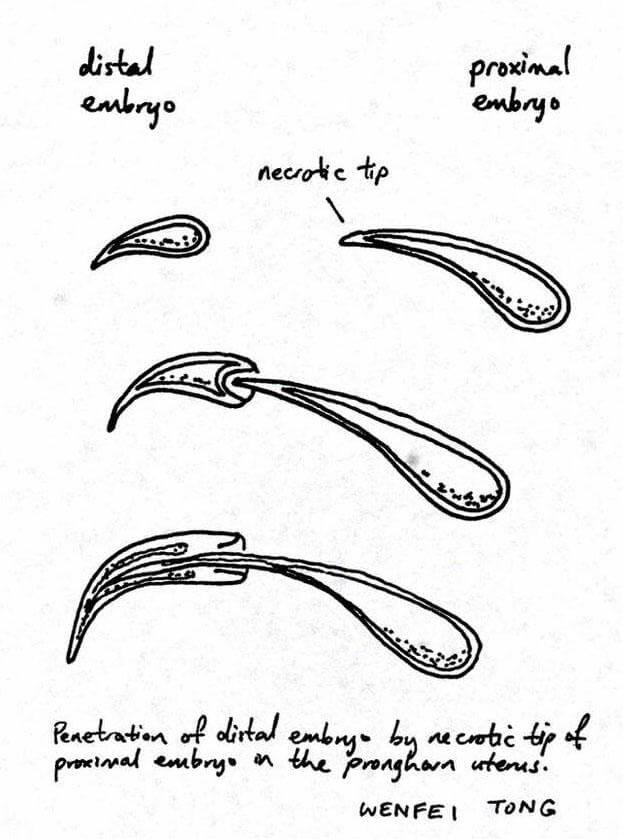

This conflict between competing children can take place at unexpected times. In addition to investing more in gestation than most ungulates, pronghorn are unusual because their twins are the only surviving winners in some pretty serious battles within the womb. Soon after fertilization, there can be more than seven developing embryos, which begin to elongate in what pronghorn biologists call the “thread-stage.” These thread-like embryos literally entangle and often knot together till they pull each other apart. Not more than seven embryos survive this first knotty battle in the womb. Later in pronghorn pregnancy, the embryos begin to implant and develop extra tissues, including a rather aptly named “necrotic tip” on one end. As the embryos grow, they begin to press into each other, and the embryos closest to the middle of their mother’s body pierce their neighboring siblings with their necrotic tips, which continue to grow into and through the speared embryo until it dies, leaving just two surviving embryos, one on each side of the pronghorn’s womb.

This conflict between competing children can take place at unexpected times. In addition to investing more in gestation than most ungulates, pronghorn are unusual because their twins are the only surviving winners in some pretty serious battles within the womb. Soon after fertilization, there can be more than seven developing embryos, which begin to elongate in what pronghorn biologists call the “thread-stage.” These thread-like embryos literally entangle and often knot together till they pull each other apart. Not more than seven embryos survive this first knotty battle in the womb. Later in pronghorn pregnancy, the embryos begin to implant and develop extra tissues, including a rather aptly named “necrotic tip” on one end. As the embryos grow, they begin to press into each other, and the embryos closest to the middle of their mother’s body pierce their neighboring siblings with their necrotic tips, which continue to grow into and through the speared embryo until it dies, leaving just two surviving embryos, one on each side of the pronghorn’s womb.

No other mammal is known to use the womb as a battleground for the survival of the fittest children, but there have been reports of one shark species that has well-developed fetuses eating each other in the womb. Every time I see some rather sweet pronghorn fawns gamboling in the sagebrush, I am reminded of the fact that even superficially harmonious scenes in nature are the result of a Darwinian “struggle for existence” which can be surprisingly inefficient.

Every week since 1991, Field Notes has inquired about Montana’s natural history. Field Notes are written by naturalists, students, and listeners about the puzzle-tree bark, eagle talons, woolly aphids, and giant puffballs of Western, Central and Southwestern Montana and aired weekly on Montana Public Radio.

Click here to read and listen to more Field Notes. Field Notes is available as a podcast! Subscribe on iTunes, Google Play, or wherever you listen to podcasts.

Interested in writing a Field Note? Contact Allison De Jong, Field Notes editor, at adejong [at] montananaturalist [dot] org or 406.327.0405.

Want to learn more about our programs as well as fun natural history facts and seasonal phenology? Sign up for our e-newsletter! You can also become a member and get discounts on our programs as well as free reciprocal admission to 300+ science centers in North America!