by Peter Lesica and Annie Garde

Winter might seem like a pretty dull time for a field botanist. No flowers, no leaves, no green except for the conifers. Ho hum. The serviceberries, chokecherries and mock orange that are so familiar by their flowers and fruits in the summer, just look like a tangle of generic bushes in winter. In the early fall, you may still find some fruits clinging to the branches or some old leaves on the ground, but as winter wears on, we’re left with only the twigs.

But a twig offers sufficient information for identification; you just have to look closely. The growth habit of the shrub, the color and texture of the bark, and the arrangement and appearance of the buds all provide clues for the botanical sleuth.

But a twig offers sufficient information for identification; you just have to look closely. The growth habit of the shrub, the color and texture of the bark, and the arrangement and appearance of the buds all provide clues for the botanical sleuth.

The first thing to notice is whether a shrub has spines or thorns. It’s also important to observe whether the branches and buds are opposite or alternate. These characteristics help place the shrub in a family.

Perhaps the most informative characters are the buds. A bud is actually a very short branch. In most species, the lowest leaves of the shortened branch are modified to form tough scales. These scales wrap around and help protect the delicate tissue that will become next summer’s leaves. Naked buds are more common in warm climates. In western Montana, only buckthorn, dogwood and poison ivy lack scales. Generally there are two or more scales covering each bud, and these may be arranged like numerous overlapping shingles or paired and meeting edge to edge. Willows are unique in that they have only a single bud scale.

I used to notice buds for the first time each year in about February, during, say, a chinook, and I’d worry that they’d been fooled by old man winter. But I was wrong. They’d been there all along. Buds are formed in the summer and become dormant in the fall in response to lower temperatures. And buds are winterized; the tissues are filled with sugars that act as antifreeze, and the scales prevent drying out. As the days become longer and warmer, the leaves inside the bud expand and the scales fall away.

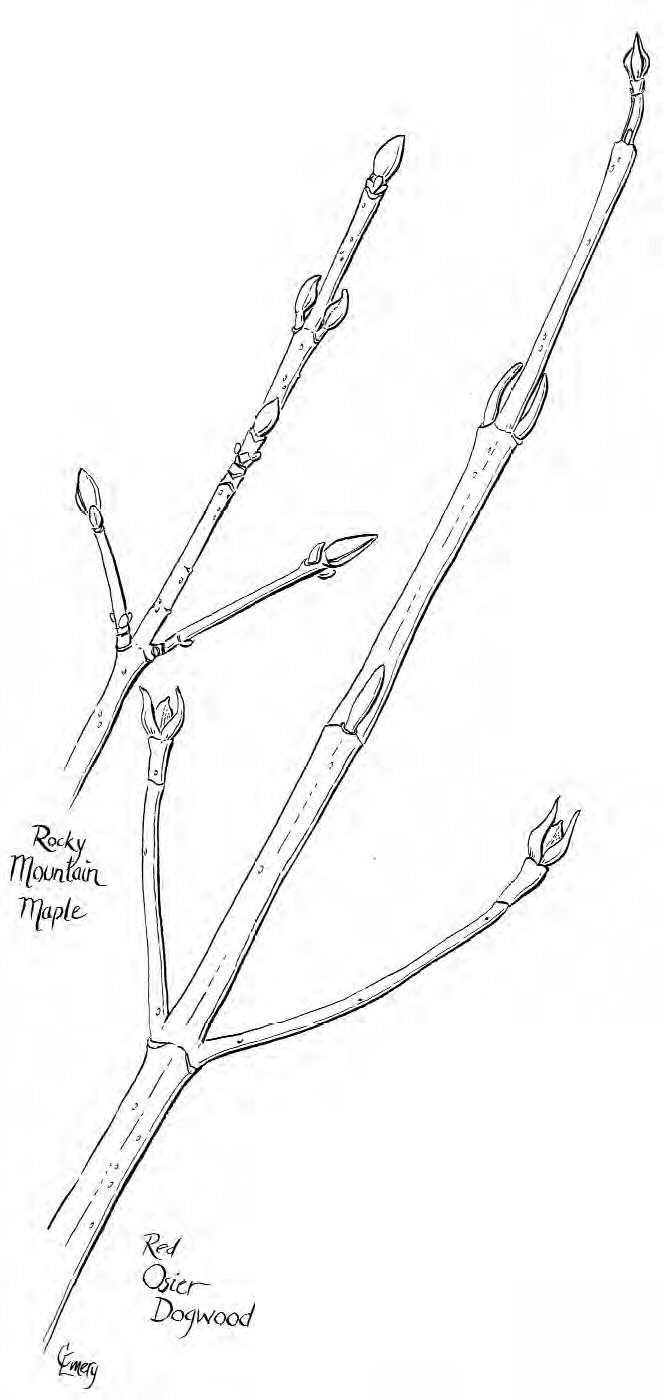

So how can these features tell us what’s what? A common shrub with smooth, bright red twigs and opposite buds and branches could be red osier dogwood or Rocky Mountain maple. The difference is that the maple has paired bud scales, while the dogwood had naked buds enclosed by little baby leaves. Among the shrubs with spines or prickles, roses, raspberries, and gooseberries are common. Roses have small shiny buds and the base of some of the thorns resembles a white shield. Gooseberries always have stout thorns just below the buds, while raspberries do not.

So, see? When the snow is lousy or nonexistent, you can still have fun. Grab your winter shrub field guide, an exacto knife and 10-power hand lens and head for the hills, as long as they have bushes on them. I can now recognize seven species of common shrubs on Mount Sentinel in the winter. And if you see me up there squatting in the bushes, don’t get the wrong idea. I’m simply examining these woody plants in their winter attire.

Illustration by Claire Emery, emeryart.com.

This article was originally published in the Winter 2007-2008 issue of Montana Naturalist magazine, and may not be reproduced in part or in whole without the written consent of the Montana Natural History Center. ©2007 The Montana Natural History Center.

Click here to read more articles from Montana Naturalist magazine.

Want to learn more about our programs? Sign up for our e-newsletter! You can also become a member and get discounts on our programs as well as free reciprocal admission to 300+ science centers in North America!