by Rob Rich

In the Lolo National Forest (LNF) just outside Missoula, Sarah Clark sloshes up Miller Creek, feeling for loose cobbles and deep pools with each step. She parts branches of red-osier dogwood as if swimming the breaststroke, taking care not to whip me, sloshing behind her, in the face. “This project has been some of the most intense of bushwhacking I’ve ever done,” Sarah says with a smile, “and I’ve done a lot of bushwhacking.” I grab a taut branch she’s held for me, and we each do a doubletake to ensure it’s not gnawed.

Sarah is volunteering with the National Wildlife Federation (NWF), and she is looking for sign of the North American beaver (Castor canadensis)—chews, dams, lodges, food caches, scent mounds, canals, scat—and, of course, the living rodents themselves.

The quest for beaver sign is nothing new; two centuries ago mass commercial trappers were so effective in their reconnaissance that beavers came close to extinction across the entirety of their range. But those early seekers had it easy, because while beavers are certainly elusive and nocturnal, their habits are predictable and their works hard to hide. And, prior to European settlement, beavers were everywhere; between the Arctic tundra and the Mexican deserts and the Atlantic and the Pacific, up to 400 million were estimated to exist.

Thankfully, beavers are recovering, and today their populations hover around 15 million. But, now that people have passed into the seventh human generation since the beavers’ pre-Fur Trade heyday, there is a greater concern than numbers alone suggest: many of us have forgotten how to see beavered landscapes, no longer able to read tiered floodplains with swollen stretches of stream, each circled with profuse willows re-sprouting from beaver herbivory. It is certainly normal for beavers to move on to new sites as their choice woody foods and building materials diminish, and this dispersal provides a cyclic succession between stream, wetland, and meadow habitats that is fascinating to discern. Many early settlers knew how these mosaics were made; but many also ditched, drained, or destroyed the beaver-cleared wetlands for their own homesteading, which abruptly halted evolution of the habitat. This complete erasure or ending of beavered landscapes is not normal, and over time such anomalies have diminished our knowledge about the distribution and density of beavers, past or present. We might call it a kind of beaver amnesia, a grave forgetting that some of the most precious landscapes where we live, work, and play have been without their creators.

But climate change is giving us reason to remember. With the prospect of less reliable snowpack, more extreme fire seasons, and warmer, less abundant water, there are new motives to seek and value beavers again. In November 2018, the Fourth National Climate Assessment even gave beavers a nod, and for over three decades, a growing body of peer-reviewed research has proven that beavers are worth far more than a commodified thing like a pelt for a hat; they’re a process that’s required to create dynamic, highly functional habitats we can’t replicate. In this beavers are like wildfires: both are necessary, restorative agents of change that have renewed Montana’s landscapes for millennia, and neither can be suppressed without consequences. So as scientists from varied disciplines ask tough questions about how our watersheds will adapt in the face of uncertainty, they’re starting to spell out a shared answer: B-E-A-V-E-R.

Sarah Clark (right) takes a midstream bushwhacking break with Marcia Brownlee, the Program Manager for the National Wildlife Federation’s Artemis Initiative, which aims to engage sportswomen in the protection in the wildlife and public lands. Photo by Rob Rich.

In the 1980s, Greg Munther, a retired Fisheries Biologist and District Ranger for the U.S. Forest Service, had a hunch that beavers could indeed answer some of Montana’s mounting water concerns. He knew that native tribes like the Blackfeet had long valued the beavers’ ability to store water in the arid, fickle climate where the Rockies met the Plains, and, after lamenting the absent rodents and their relict habitat at his post on the Ninemile Ranger District, he determined he couldn’t resolve the problems alone. So Munther experimented with relocating beavers from private to public land on his District, and he protected them with trapping closures. These were informal trials, but he generally found the beavers to increase the quantity and quality of aquatic habitat. Munther’s results were affirmed with new energy in 2016, when the LNF worked with the Clark Fork Coalition (CFC) to complete a Watershed Vulnerability Assessment. As the assessment focused on bull trout (a threatened species under the Endangered Species Act) and water supply, they found that the watershed connectivity and complexity that beavers provide might offer hope against the heat predicted in the decades ahead.

Munther’s vision, echoed by the Watershed Vulnerability Assessment, paved the way for the keystone partnership that Sarah Clark was supporting on Miller Creek. This partnership includes core contributions from CFC and NWF, who are working with other organizations and volunteers to advance three distinct but closely linked goals. The first goal is the Watershed Restoration Citizen Science Project, which is designed to assess where, when, and to what extent beavers are occupying western Montana watersheds. Amy Chadwick, a Senior Ecologist and beaver expert with Great West Engineering, kicked off the process with a computerized model suggesting where beavers might be, based primarily on the valley width and stream slope. That helped, because we know beavers prefer slow streams that aren’t too steep and have wide floodplains to flood, but there was more to learn on the ground: Where were the hardwood shrubs that beavers would eat? Where were the deep pools that wouldn’t freeze to bottom in winter? And fresh sign of live animals? That was needed too, because we know that beavers—who thrive by going against the flow—rarely follow the rules. Chadwick’s model thus became a guide for surveys to reveal the presence or absence of real beavers in real time, so that we might see where beavers can best help us heal watersheds at risk from becoming too straight or too hot. Though Sarah Clark and the seven other volunteers in the adult program haven’t found any fresh beaver sign on Miller Creek yet, they’ve documented a moose, a charismatic beaver beneficiary who seemed keen for a wetland on a hot summer day.

Readied with tape measures, depth sticks, clinometers, cameras, bear spray, and a whole lot more, this crew of intrepid young citizen scientists ascends Lolo Creek to seek sign of the mighty beaver. Photo by Florie Consolati.

I smiled when Sarah said that childhood nature forays were her closest analogue to bushwhacking for beavers, because there is actually a youth component to this citizen science project as well. With leaders from Montana Conservation Corps (MCC), teams of middle schoolers have focused their beaver scouting in reaches of Lolo, Miller, and Fish Creeks in the LNF, as well as the Spotted Dog Wildlife Management Area near Deer Lodge. This youth program sparked the citizen science project in 2018, and when CFC worked with LNF’s Traci Sylte to earn a $25,000 Citizen Science Competitive Funding Program Grant this year, it allowed them to expand their efforts. In 2019 alone, 36 middle schoolers surveyed 58 quarter-mile long reaches of stream, racking up 172 data points across 14.5 miles, all of them sloshed with waders. As CFC Education Manager Lily Haines and MCC Youth Programs Manager Nick Ehlers have watched their five 2019 teams build confidence with the hands-on field skills in hydrological measurements, backcountry navigation, and wildlife biology techniques required to achieve these results, they have grown increasingly thrilled with the promise of this partnership. There are many insights to glean from the data, but comparisons will be especially valuable with the Fish Creek watershed, which remains one of the few drainages in the state that is closed to beaver trapping, thanks to Greg Munther. When the kids encountered beaver sign at Fish Creek this summer—after all their schlepping and measuring and navigating—they felt like they had rediscovered a great treasure. And they had.

Because LNF doesn’t have the time or resources to groundtruth all their models, these citizen scientists are providing nuance that’s inspiring the partnership’s second goal: to pursue some of the challenging research questions for beaver management, especially those at the intersections of beavers, people, and fish. Montana’s native fish are especially sensitive to water loss and warming in their streams, and some scientists have been concerned that beaver dams could be barriers that seal their fate. But there has been abundant research proving that beaver dams are more porous than we think, and that most steelhead trout and Pacific salmon actually flourish with the variety of overwintering and rearing habitats that beavers provide. There is more to learn in regards to beavers’ specific relationship with Montana’s grail species—the bull and westslope cutthroat trout—so Ph.D. candidate Andrew Lahr is working with Dr. Lisa Eby, Professor of Aquatic Ecology at the University of Montana, to explore these interactions. Fish and wildlife managers can no longer assume that current conditions will persist in the future, and Lahr will be chasing questions to see how beavers can help ensure that Montana’s native fish have enough water to survive into the next century, and beyond.

As Lahr’s research evolves, it’s worth remembering that beavers and fish as we know them today have been co-evolving too, for the last 7.5 million years they’ve shared in North America. But as humans have more recently colonized the beavers’ haunts, conflicts do happen, and this project’s third goal aims to resolve conflicts non-lethally. Because trapping beavers is a temporary, ineffective approach that only makes a void for dispersing beavers to fill, CFC’s Restoration Director Will McDowell and Beaver Technician Elissa Chott have spent the summer encouraging landowners to use proven alternatives for success: wire-wrapping to deter gnawing of choice trees, fencing to prevent culvert plugging, and pipe/ fence “flow devices” that allow landowners to lower their flooding risk. To a beaver, a road with a culvert is basically just a dam with hole, but these tools use knowledge of beaver ecology to find the compromise. With support from Defenders of Wildlife, CFC eventually aims to build up a cost-share program to incentivize landowner participation and tolerance that can be adapted across the state.

As Lahr’s research evolves, it’s worth remembering that beavers and fish as we know them today have been co-evolving too, for the last 7.5 million years they’ve shared in North America. But as humans have more recently colonized the beavers’ haunts, conflicts do happen, and this project’s third goal aims to resolve conflicts non-lethally. Because trapping beavers is a temporary, ineffective approach that only makes a void for dispersing beavers to fill, CFC’s Restoration Director Will McDowell and Beaver Technician Elissa Chott have spent the summer encouraging landowners to use proven alternatives for success: wire-wrapping to deter gnawing of choice trees, fencing to prevent culvert plugging, and pipe/ fence “flow devices” that allow landowners to lower their flooding risk. To a beaver, a road with a culvert is basically just a dam with hole, but these tools use knowledge of beaver ecology to find the compromise. With support from Defenders of Wildlife, CFC eventually aims to build up a cost-share program to incentivize landowner participation and tolerance that can be adapted across the state.

All three of these goals—the citizen science, the research, and the conflict prevention— seem like a lot of work. But they’re worth it, because although wetlands cover a mere two percent of the landscape here in the Intermountain West, they hold a whopping 80 percent of its biodiversity. Every drop is priceless, and this multifaceted partnership is proving that what’s important is coming together around this shared resource. Beavers keep wetlands working, and their legacy is not only etched within the topography and hydrology of the continent, but it’s also enabling the lives of countless species who thrive where land and water meet and sum their parts. The Common Yellowthroat singing whichity-whichity-which in the willows. Plus the Wood Duck with her young, scooting through the sedges. Plus the white-tailed deer drinking from a still pool, and the Columbia spotted frog making a splash. The beaver thrives within—and creates—these convergences, and with leaders like Sarah Bates, Senior Director for NWF’s Western Water Initiative, we are getting better at mimicking the masters. Bates has said this partnership is about “laying the groundwork for beavers to return to a receptive landscape,” and it’s true: this is the foundation we need, working with and for the keystone, putting beavers back on the map.

—Rob Rich is a naturalist, writer, educator, and beaver believer. His work has appeared with Earth Island Journal, High Country News, Sierra, Camas, and other publications.

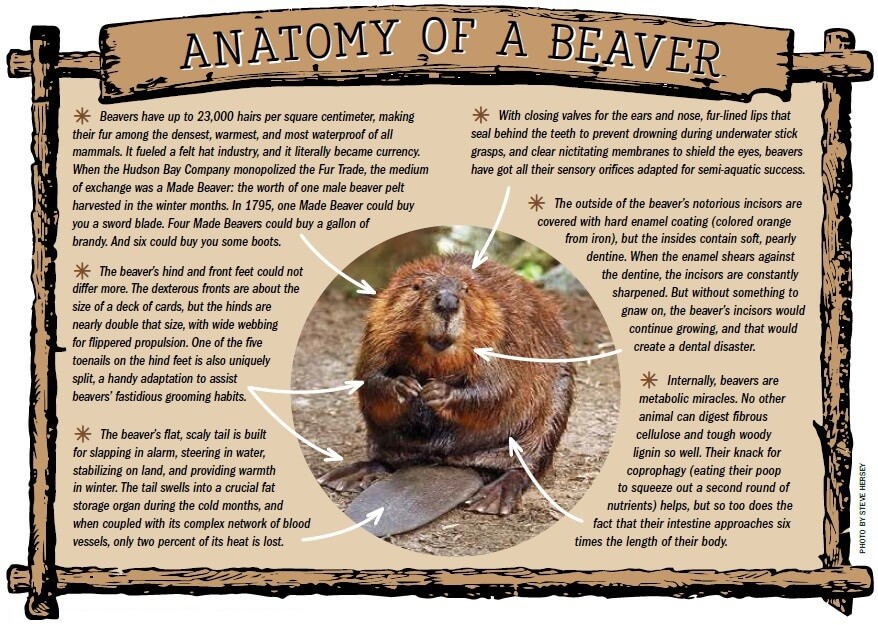

One species of prehistoric beaver was as big as a black bear, and another was a burrower the size of a prairie dog. Neither of them built dams, and neither survives today. The modern-day North American beaver fills a different niche, centered on a semi-aquatic lifestyle with chiseled teeth fit to cut wood, and engineering behaviors to impound water. These highly specialized, successful adaptations afford safety from predators and access to food, and in the process of modifying watersheds into a home where they can survive, today’s beavers are keystone species who create complex, diverse habitats upon which countless other species depend. Photo by Rob Rich.

Want to learn more about beavers?

Be sure to check out Ben Goldfarb’s Eager: The Surprising, Secret Life of Beavers and Why They Matter. And young readers of all ages should get their hands on Dorothy Hinshaw Patent’s At Home with the Beaver: A Story of a Keystone Species.

This article was originally published in the Fall/Winter 2019 issue of Montana Naturalist magazine, and may not be reproduced in part or in whole without the written consent of the Montana Natural History Center. ©2019 The Montana Natural History Center.

Click here to read more articles from Montana Naturalist magazine.

Want to learn more about our programs? Sign up for our e-newsletter! You can also become a member and get discounts on our programs as well as free reciprocal admission to 300+ science centers in North America!