Story and photos by Nick Littman

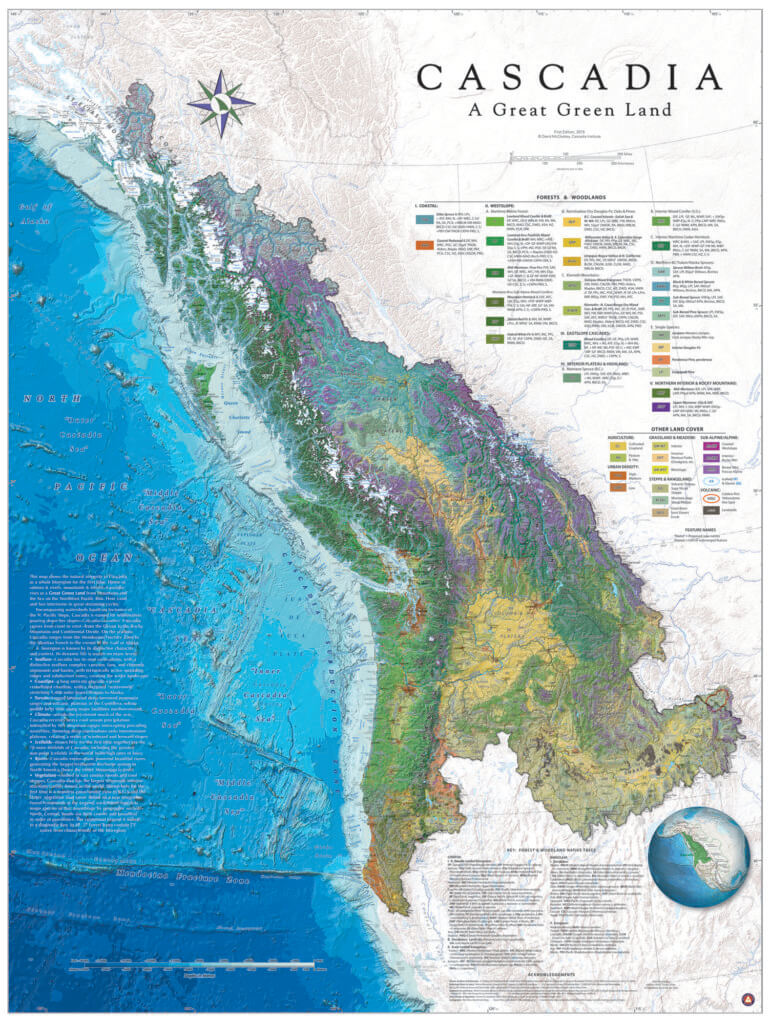

On my living room wall, I have mounted a many-colored map. I stop to look at it often, not to see where I am going, but to remember where I am.

The map does not show me much about topography, or where highways go, or how big Seattle is compared to Missoula. What the map shows me is where I exist within Cascadia—my bioregion.

Bios is Greek for life, regia is Latin for territory. My bioregion or life territory is an area defined by its natural systems, a region governed by abiotic and biotic commonalities—geology, climate, elevation, flora, and fauna—instead of arbitrarily-drawn political boundaries. In a bioregion, the cycles of life are intricately intertwined—cedar and fern, spruce and caribou, white-bark pine and Clark’s Nutcracker; all the relationships within the region, including the human ones, are adapted to and depend upon the character of the land. Although my home of Missoula sits within a dry, rain-shadowed valley, the character of my region, this “great green land” of Cascadia, begins and ends with the ocean.

The dense canopy of old-growth rainforests limits what plant life can survive on the forest floor; western sword ferns are one of the species that thrive in deep shade.

In northern Cascadia, the Pacific provides the water, and the mountains—the Cascades, Coast Range, Columbias, and many smaller ranges—receive it and return it through their rivers. The falling of this water supports some of the most magnificent forests in the world. Before moving to Montana, I knew only of the forest that is emblematic of Cascadia: the dripping and decaying coastal rainforest stretching from northern California to southeastern Alaska. However, as I began to explore the broader geographical patterns of my bioregion on foot, walking into the Bitterroot, St. Joe, Cabinet, Selkirk, and Purcell mountains, I’ve been introduced to the two inland forests of my region: the interior maritime forest and the snow forest.

The map of Cascadia helps me to notice patterns within my bioregion. At first these patterns are only interpreted from the map: I can see that the interior maritime rainforest is labeled as a “maritime cedar-hemlock” forest and the snow forest is labeled as “upper montane.” As I’ve lived in the Inland Northwest longer, I’ve begun to ground-truth these patterns and learn what lines and shades look like when transposed onto earth and bark and mountain. It is this process of observation and discovery that has helped me to acquire a sense of connectivity and scale. Visiting these patches of interior maritime forest, the Ross Creek Cedars beside the Cabinets or the Kokanee Creek Cedars in the Selkirks, has helped me to appreciate how far these forests stretch and how connected they are, both to each other and to the natural systems that have helped to create them.

The interior maritime forest is the largest inland rainforest in the world. It is a broad diagonal stroke on the map that includes land in three states and one province. The forest begins in the south along the Selway and Lochsa rivers in Idaho. In the north it disappears just past Prince George, British Columbia, in the Cariboo Mountains. The variation across this span is significant: more rain falls in the summer as you move further north, and the size and maturity of the northern cedar-hemlock forests I’ve seen in the Purcells cannot be rivaled by the remaining old-growth stands within Montana. However, walking up Trout Creek from the Clark Fork Valley to the crest of the Bitterroots, or up the East Fork of the Bull River from the Bull River Valley to the top of the Cabinets, or up Kokanee Creek from Kootenay Lake in the Selkirks will all yield a similar floristic shift from interior maritime forest, to snow forest, to no forest.

Late spring—mid-June—is the time I enjoy this landscape the most. The creeks are deafening and water seems to be coming from the very pores of the mountain. From the valley, I climb up a steep V-shaped valley under a canopy of giants. Here, the earth is spongy underfoot—carpeted with a continuous layer of moss. Red, green, blue, and white lichens provide vibrant color to the forest, clinging to the trunks of live and dead trees. All around me many species of fern and the tall bristled stalks of Devil’s club populate the forest floor, but few other understory species can live beneath the overhead shade. I walk easily through the dappled light of this forest, keeping my eyes up to find the tops of the trees towering above me.

A fiddlehead fern opens up along the Selway River, at the southern reaches of the interior maritime forest.

The giants above me are the overseers of this apex forest—the broad-trunked western redcedar (Thuja plicata) and drooping-crowned western hemlock (Tsuga heterophylla). With the right conditions, redcedars can grow to 150 feet tall and 10 feet in diameter and live for up to 1000 years, and hemlocks can stretch to 120 feet tall and live for 500 years. These trees create one of the few true “old-growth forests” that you can find in the Inland Northwest. They are able to flourish 350 miles from the coast, weathering the heavy snows and dry, hot summers of the interior due to the precise climactic conditions created by the mountains. In the spring, snowpack nourishes the trees through May and rain falls in June. When the trees enter the parched summer season their roots are kept hydrated by the many creeks, trickles, and seeps that drain the higher-elevation snow forest.

The giants fall away as I reach the snow line; the broad cedar and hemlock trunks are replaced by the skinny spires of subalpine fir, Engelmann spruce, and lodgepole pine, trees that are much better at sloughing off a snowpack that will reach eight to twelve feet deep. I have entered the upper montane zone—the snow forest. Later in the summer, a scraggle of huckleberry bushes will make it challenging to move through here without stopping, but in June I crunch along the crust of snow and notice how it provides a continuous drip of water to the photosynthesizing trees. In places where the snow thins, glacier lilies splash the white canvas with yellow.

I continue walking steeply through the snow forest for several thousand feet up the mountain. From north to south across its range, the habitat the snow forest creates supports some of our most charismatic North American mammals—gray wolves, grizzly bears, wolverines, and mountain caribous (mountain caribous are mostly found in the northern Columbia Mountains, though they have been found in the southern Purcells which dip into northwestern Montana). Wolves and grizzly bears mostly use this habitat when it is snow-free, but wolverines and caribou have both adapted to living on the snow. Caribou can spread their hooves wide to act as snowshoes, and in mid- to late winter the heavy snowpack allows them to reach the bryoria lichen (old man’s beard) higher in the trees. Wolverines scavenge widely for carcasses across the subalpine and alpine, and their large paws in comparison to their bodyweight keep them above the snow.

The trees thin out as I reach higher elevations and then stop altogether. In the Columbia Mountains—the Selkirks, Purcells, Monashees, and Cariboos—glaciers hang to the mountaintops, remnants of the last ice age. High on the ridgetops, snowdrifts last into July and August. When they melt, the meadows explode into a tapestry of color, the long-awaited expression of summer.

At the crest of the mountains a broad sweep of life-producing forest falls off below me. To the north and south this wide green ribbon stretches for hundreds of miles, supporting one of the most diverse and unique ecosystems in this part of the world. Looking west I can thank the distant Pacific Ocean for the nourishing clouds it sends my way. The creeks below me trickle into rivers that flow into the mighty Columbia River, returning the waters to their source, completing the cycle. Putting this place within a bioregional context reminds me that the processes that sustain each of the thousands of species within these forests are vast and far more complex than I will ever be able to understand. I must be content to observe and to record, to appreciate and to listen. Little by little, the many-colored map of the “great green land” comes into focus.

Nick Littman loves to explore, teach, and write about the intricacies of place. He teaches for the Wild Rockies Field Institute and the Missoula Writing Collaborative.

The wide valley surrounding Glacier Creek in the Purcell Mountains of British Columbia is filled with extensive cedar-hemlock forests, while the higher elevation snow forest is already living up to its name in late September.

This article was originally published in the Winter 2017-2018 issue of Montana Naturalist magazine, and may not be reproduced in part or in whole without the written consent of the Montana Natural History Center. ©2017 The Montana Natural History Center.

Click here to read more articles from Montana Naturalist magazine.

Want to learn more about our programs? Sign up for our e-newsletter! You can also become a member and get discounts on our programs as well as free reciprocal admission to 300+ science centers in North America!