Please Don’t Touch the Bison

By Janet Cass

Broadcast 7.12 & 7.15.2023

Bison herd crossing the Madison River. Photo by NPS / Jacob W. Frank, public domain.

Listen:

It must have looked like a scene in a movie Western: a herd of bison crossing a river, dust in the air, noise, splashing, all set against the grandeur of Yellowstone National Park in May. The herd included bison calves, born in late March through May that year.

When that scene occurred this year in May, a visitor to the Park interfered with a calf struggling to cross a river. The visitor didn’t see the calf’s mother, assumed the calf needed his help, and pushed it out of the river and onto a road. The calf, too young to survive on its own, began approaching people and cars, hazardous for all concerned. National Park Service staff tried unsuccessfully to reunite the calf with the herd, and regulations ruled out transporting it to a sanctuary. Park staff euthanized the calf as the only remaining option.

The way this was reported by some media outlets implied the calf’s presumed rejection by its mother and herd was due to its having been handled by a human, but the situation may have been more complex.

“[It is] really tough to determine if that bison calf had already been rejected by its mother for another reason [besides having human scent on it].” So says Dr. Jared Beaver, Certified Wildlife Biologist and Extension Wildlife Specialist at Montana State University. “Young do get rejected for a multitude of reasons. For example: The offspring was sick or injured and mother believed it wouldn’t make it. Mother is young and feels ill-prepared or lacking maternal instincts. Mother is in poor condition and unable to take care of herself and the young … with bison it is rare to have twins but a lot of times in those situations the mother will abandon the weaker individual. But yes, interference very early in [the] bonding stage can also cause abandonment. It’s tough to say that the calf was rejected solely because the human intervened/touched the animal.”

Retired bison rancher Lee Graese’s hunch is that the calf had already been rejected by its mother before the visitor saw it, because, he says, “If that calf’s mother had been around, there’s no way the guy could have gotten near the calf.” He’s seen bisons’ fierce maternal protection of their young first-hand, having raised the animals for 29 years at NorthStar Bison in Wisconsin.

It’s also possible the mother was dead, but it’s unlikely the calf would be raised by another adult female in the herd because “a bison cow typically won’t accept an orphaned calf,” says Graese. Or, perhaps calf and mother became separated during the river crossing, in which case the mother typically and quickly returns to the river to retrieve her calf.

What if the human hadn’t intervened? The calf might have drowned, been hit by a car, starved, or been eaten by a large carnivore. About 25 percent of bison calves in the Park die before they’re a year old, Dr. Beaver reports. That’s part of life in the wild. “Especially in the Park,” he notes, “with severe weather events and large predators on the landscape.”

Although it’s not known why the calf was crossing the river apparently unattended, interference by the well-meaning but uninformed human created problems. Maybe the mother returned to the river only to find her calf gone because the human moved it. And the human risked being killed or seriously injured by a member of the herd by getting close to it. The human pled guilty to a federal charge and was fined.

Park regulations say to stay at least 25 yards away from all animals, including bison; at least 100 yards—that’s one football field—away from bears and wolves; and recommend viewing wildlife from inside a car.

And if you see a wild animal you think is injured or abandoned—please, contact authorities like your area’s National Park Service office, Humane Society, zoo, or nature center. Alerting people who are experienced at helping wildlife thrive instead of interacting with wild animals yourself provides the best chance of ensuring a healthy future for all creatures.

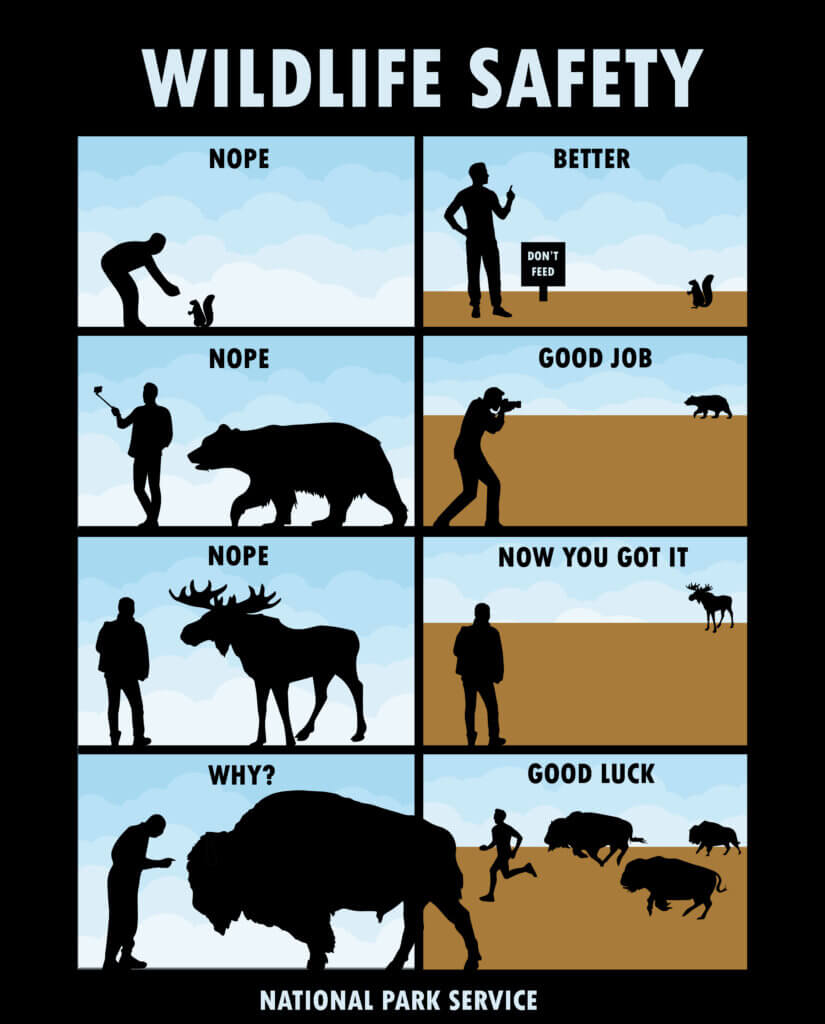

A humorous (but helpful) take on wildlife safety. NPS image.

Every week since 1991, Field Notes has inquired about Montana’s natural history. Field Notes are written by naturalists, students, and listeners about the puzzle-tree bark, eagle talons, woolly aphids, and giant puffballs of Western, Central and Southwestern Montana and aired weekly on Montana Public Radio.

Click here to read and listen to more Field Notes. Field Notes is available as a podcast! Subscribe on Apple Podcasts or wherever you listen to podcasts.

Interested in writing a Field Note? Contact Allison De Jong, Field Notes editor, at adejong [at] montananaturalist [dot] org or 406.327.0405.

Want to learn more about our programs as well as fun natural history facts and seasonal phenology? Sign up for our e-newsletter! You can also become a member and get discounts on our programs as well as free reciprocal admission to 300+ science centers in North America!