Rain Shadow

by Alison James

Broadcast 5.6 & 5.11.2018

Infograph by Eileen Chontos.

Listen:

I love driving from Missoula to Helena or Great Falls or Bozeman, over the big passes of the Continental Divide and along some of our country’s most spectacular rivers. On the west side of the Divide, we pass green foothills, huge ponderosas and larch, and soaring bald eagles and osprey. Dropping down onto the east side, we start to see grasslands, sage brush, mule deer and pronghorn. Travelers in Montana know that the climate on the east side of the Continental Divide is suddenly and significantly different than on the west side. Wondering why is a good thing to ponder on a long drive.

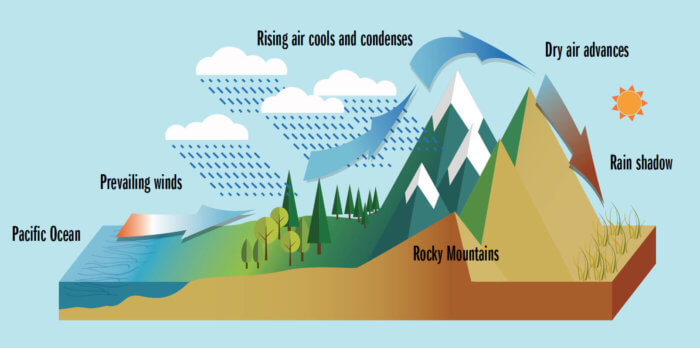

Though many variables impact climate, one of the most important factors in the immediate difference between the western side of the Rockies and the eastern side is the effect of rain shadow. The American Meteorological Association defines rain shadow as “a region of sharply reduced precipitation on the lee side of an orographic barrier, as compared with regions upwind of the barrier.” The lee side, as sailors and mountaineers know, is the side the wind doesn’t hit. And an orographic barrier is just a meteorologist’s way of saying “the mountains.” We have many beautiful orographic barriers in Montana.

In western Montana, warm, wet weather systems blow in from the Pacific Ocean. As those systems travel across the landscape, the mountains force the air up to higher elevations. As the air goes higher, it cools and condenses, dropping rain and snow on the western slopes. The clouds collect against the mountainsides and get wrung out like a sponge. As the air moves over the mountains and down, it dries out. On the east side, the now-dry air actually absorbs moisture from the earth, making the landscape all the more arid.

The average yearly precipitation in Helena is 11 inches — just shy of desert. Kalispell gets about 15 inches of precipitation a year, and Missoula gets about 14 inches. As that warm, ocean air moves west and up, snow and rain hydrates western Montana. On a walk in the woods, you’ll find ferns and cedar trees, mushrooms and huckleberries. But if you take a hike on the other side of the divide, you’ll see organisms adapted to survive in dry climates: prickly pear, sage brush, limber pine, rattlesnakes. Many species, like bears, elk, deer, cottonwood trees, ponderosa pine, knapweed, and people, can thrive on both sides of the divide.

The rain shadow effect can be seen all over the world. The plains of eastern Washington and Oregon are in the rain shadow of the Cascades. Nevada and California’s massive deserts (like Death Valley) are in the rain shadow of the Sierra Nevada range. The Tibetan plateau is in the rain shadow of the Himalayas. And many Montanans claim a favorite side of Glacier National Park—the green, verdant west side versus the spare, windblown expanses of the east side. They are two different worlds, hinged together at the top of the Rocky Mountains.

As I travel from west to east I’m reminded of the words of Wallace Stegner: “…the Rocky Mountain West is a region of bewildering variety. Its life zones go all the way from arctic to subtropical, from reindeer moss to cactus, from mountain goat to horned toad. Its range of temperatures is as wide as its range of precipitation; it runs through twelve degrees of latitude and two miles or more of altitude. It is bald, alkali flats, creosote-bush deserts, short-grass plains, irrigated alluvial valleys, subarctic fir forests, bare stone.”

Driving over the mountain pass, I feel grateful. I’m grateful for good tires to navigate these mountain roads in changing weather conditions. And I’m grateful to live in a place where life zones come together, in the rain and in the rain shadow, where we can see so much variety and beauty, sometimes within just a few miles.

Every week since 1991, Field Notes has inquired about Montana’s natural history. Field Notes are written by naturalists, students, and listeners about the puzzle-tree bark, eagle talons, woolly aphids, and giant puffballs of Western, Central and Southwestern Montana and aired weekly on Montana Public Radio.

Click here to read and listen to more Field Notes. Field Notes is available as a podcast! Subscribe on iTunes, Google Play, or wherever you listen to podcasts.

Interested in writing a Field Note? Contact Allison De Jong, Field Notes editor, at adejong [at] montananaturalist [dot] org or 406.327.0405.

Want to learn more about our programs as well as fun natural history facts and seasonal phenology? Sign up for our e-newsletter! You can also become a member and get discounts on our programs as well as free reciprocal admission to 300+ science centers in North America!