by Charles Miller

Spring is here, and with this season comes a fascinating panorama of activity between insects and flowers. The colorful flowerbeds and fields of wildflowers present an irresistible space that actually reflects the beauty of the insects themselves. This intricate partnership between flowering plants and insects has occurred for over a hundred million years.

The bargain between flowers and insects is of a serious nature: survival. It requires a trade of food in exchange for pollination. All of us can—and do—enjoy the show at a macro level, but what might we find if we look closer, delving into the minutiae of this plant-insect interaction?

Pollinators and Winter Survival

Bees are usually considered the champion pollinators, but butterflies and moths do their fair share. Although their goal is food, without the pollinating they do while collecting nectar we would find our food sources in jeopardy. Many of the wild bumblebees and commercial honeybees are in serious decline worldwide due to habitat loss and diseases caused by fungus and mites. All of us can help by planting butterfly gardens and providing shelters and hibernacula (in Latin, “tent for winter quarters”) for them.

Getting through the winter in Montana can be challenging for insect pollinators. Only one butterfly, the Monarch, avoids the winter by true migration to Mexico and coastal California. Monarchs cycle quickly through several generations over the summer, the last of which repeats the mysterious migration south without ever having been there! Monarch butterflies can be observed here in Montana and a few have been seen at the Native Plant Garden at Fort Missoula. Milkweed, their host plant, can also be found in this area.

Butterflies will hibernate in all four life stages: egg, caterpillar, chrysalis, or adult. Some butterflies that hibernate in the caterpillar stage construct hibernacula on a host plant, such as the willow. In the spring the caterpillars leave the shelter and feed on the new growth. Blues, swallowtails and whites overwinter as chrysalises. Anglewings, tortoiseshells, and our state butterfly the Mourning Cloak can hibernate in the adult form. In fact, Montana has at least eight species that do this. How do they do it? Most will seek shelter inside a loose hay bale or find an open barn or building. Some will find a hollow tree or sheltered crevice to crawl into and hope for a mild winter. Look and listen (more on that later!) for the Mourning Cloak cruising on a late winter or early spring jaunt in Montana.

Special Structures Used by Bees and Butterflies

Bees are the best-known pollinators, but butterflies are probably more interesting to watch, and do their fair share of pollination. Many butterflies have stunning colors and wing patterns—and none of them bite, sting or emit a foul odor. They flit about in sunlit fields and gardens begging to be watched. Honeybees, bumblebees, butterflies, and other insects that collect pollen have a full toolbox consisting of leg baskets, brushes, and sweeping devices to accomplish the task. Some bees are pollen shakers. Bees also collect nectar by using their tongue and a short proboscis (a tubular mouthpart used for feeding) which they fold up like a pocketknife tucked under their body when not in use. Most of the bees are fuzzy-bodied creatures with a honey crop inside their abdomen to store nectar.

In contrast, butterflies are primarily nectar-collecting insects with fairly smooth bodies and depend entirely on liquid food. They pay no attention to pollen, although they inadvertently transport some from plant to plant as they seek out nectar. The butterfly has a unique coiled proboscis which is an engineering marvel. This suction tube is watertight and very flexible lengthwise, like a zipper, so it can be extended and rolled up. It has a built in oiler, a gland that secretes and lubricates the structure as it is extended.

Some bees fly with the proboscis extended, but rolling up the proboscis into a spiral is a unique adaptation of the Lepidoptera. The rolling up occurs passively with very little energy expenditure—and a good thing, too, since it happens thousands of times each day. This circular spring is made of a natural miracle substance called resilin, which has elastic properties closer to natural rubber than any other artificial material. Biomedical research is being done with a view towards using a similar substance for artificial joint replacements.

One classic pollinating story involves a prediction by Charles Darwin, who was far ahead of his contemporaries. He was shown an orchid flower from Madagascar in which the nectar was buried deep within the long petals—about 10-12 inches deep. He predicted that there must be an insect pollinator with a proboscis long enough to reach the nectar at the bottom of the spur. Though his notion was laughed at at the time, forty years later (and more than 20 years after Darwin’s death), Xanthopan morganii, a hawkmoth from Madagascar, was discovered—with the predicted 12-inch+ proboscis. More recently this moth was finally filmed nectaring on the orchid (Angraecum sesquipedale, also known as Darwin’s orchid). See the video on YouTube.

One classic pollinating story involves a prediction by Charles Darwin, who was far ahead of his contemporaries. He was shown an orchid flower from Madagascar in which the nectar was buried deep within the long petals—about 10-12 inches deep. He predicted that there must be an insect pollinator with a proboscis long enough to reach the nectar at the bottom of the spur. Though his notion was laughed at at the time, forty years later (and more than 20 years after Darwin’s death), Xanthopan morganii, a hawkmoth from Madagascar, was discovered—with the predicted 12-inch+ proboscis. More recently this moth was finally filmed nectaring on the orchid (Angraecum sesquipedale, also known as Darwin’s orchid). See the video on YouTube.

Another fascinating Darwinian observation involves butterflies communicating by sound. Darwin describes in The Voyage of the Beagle a distinct loud clicking sound made by a butterfly in South America. A few other butterflies have been found to emit sound, usually a click something like a Fourth of July sparkler or small firecracker. One butterfly family, Hamadryas, includes several species of Cracker butterflies that produce clicking or clacking sounds. They can occasionally be found in Florida and Texas but are tropical South American species. The mechanism for producing this sound is suggested to be a wing-vein buckling mechanism in combination with a Vogel’s hearing organ, also on the wing.

This ability to emit sound is also apparently a characteristic of our Mourning Cloak butterfly, although only two field guides mention it. I have been listening for this click from the Mourning Cloak for almost a year with no success. Ben Gadd, a Canadian naturalist and author Handbook of the Canadian Rockies, has heard the sound of the Mourning Cloak: a single click when the butterfly takes off in flight. The next time you come across a Mourning Cloak, listen for it—and let me know if you hear it!

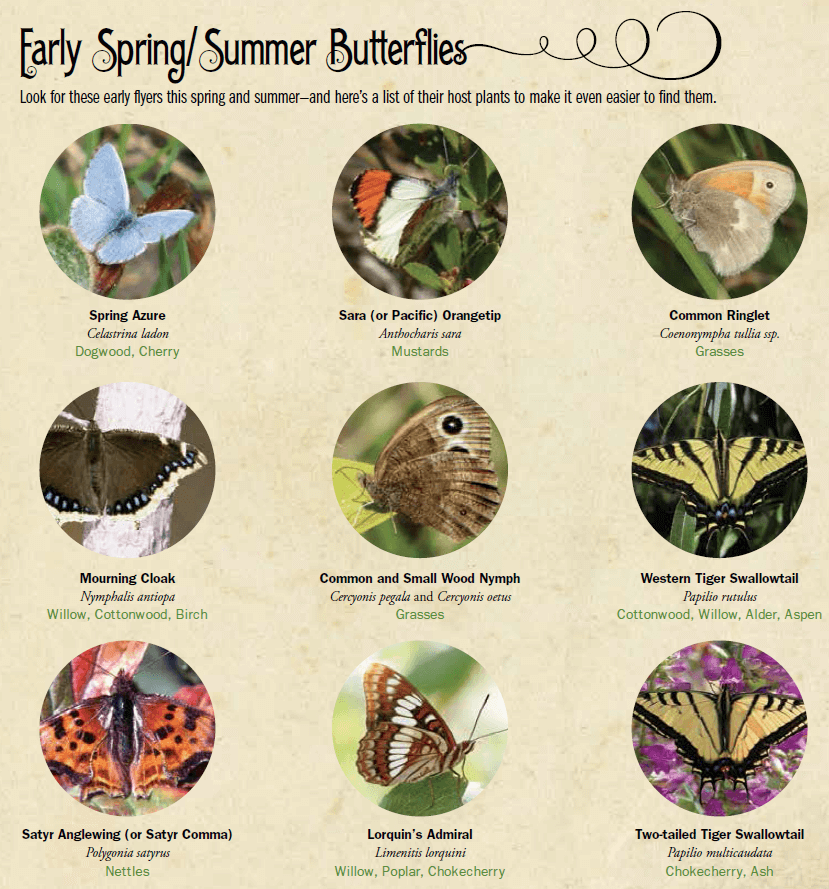

Montana Spring and Summer Butterflies

Look (and listen!) for the Mourning Cloak cruising on a sunny late winter or early spring day. Other early spring flyers are the Satyr Anglewing (also known as the Satyr Comma) and the beautiful Orange Tip. If you can capture the Orange Tip, look at the spectacular underside coloring pattern. A little later in the season, look along the Kim Williams trail in Missoula for the large Two-tailed Tiger Swallowtail. See how many butterflies you can find this summer—and think about the intricate dance they and other insects have performed with our flowering plants for the past hundred million years.

Charles Miller retired as Director of Clinical Education for the Respiratory Therapy program at Missoula College and continued to teach there part time. He also spent many years teaching about insects and birds for the Master Naturalist classes at the MNHC.

This article was originally published in the Spring/Summer 2014 issue of Montana Naturalist magazine, and may not be reproduced in part or in whole without the written consent of the Montana Natural History Center. ©2014 The Montana Natural History Center.

Click here to read more articles from Montana Naturalist magazine.

Want to learn more about our programs? Sign up for our e-newsletter! You can also become a member and get discounts on our programs as well as free reciprocal admission to 300+ science centers in North America!