Story and photos by Tim Wheeler

You’ve probably noticed them: dangling above a forest trail, covering rocks atop an alpine peak, colonizing fence posts and the bark of urban trees. These bizarre shapes and colors that decorate our world are a group of organisms, actually mini-ecosystems, known as lichens.

Lichens are an extraordinary union between two, and sometimes three, biological kingdoms. Lichen is the specific combination of a fungus, an alga, and the occasional cyanobacterium (blue-green alga), living together in a symbiotic relationship – thriving where the individual part alone could not. Imagine your dog, the tulips in your garden, and the mushrooms on your salad joining together to form a new, fully functional organism!

In this unique association, the fungus provides the housing that supports the algae and/or cyanobacteria. In return, the algae photosynthesize (just like green plants) and provide the fungus with essential sugars. Taking advantage of each partner’s abilities, lichens can be found in the most extreme environments, such as sun baked rocks and exposed vertical cliffs.

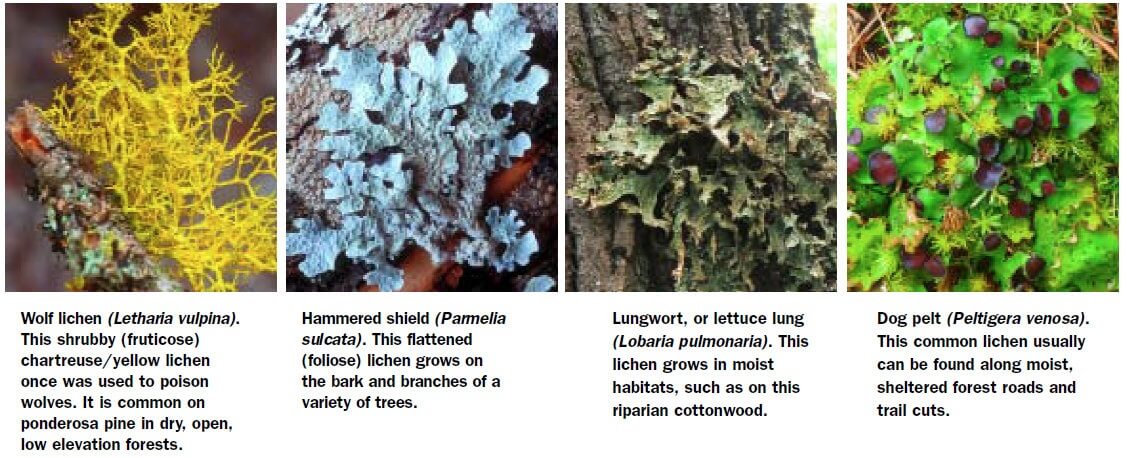

There are about 2,500 lichen species in the Pacific Northwest alone, and they come in all shapes, sizes, and colors. To make identification easier, taxonomists have divided lichens into three main groups: foliose, or leaflike, lichens; fruticose, or shrublike, lichens, and crustose, or crustlike, lichens. The foliose and fruticose lichens often are called macrolichens, while the crustose lichens are called microlichens. Although lichens can be found on almost any substrate in any environment, they reach their greatest diversity on the trees, rocks and soils of moist forests.

Lichens play many important ecological roles in the natural world. They act like sponges, capturing dust and water particles from the air and depositing these nutrients in the surrounding environment – in effect preventing erosion, nutrient loss, and desiccation. Some even fix nitrogen, fertilizing the very soil in which they and neighboring plants and trees grow.

Lichens also provide food for mammals and insects. During snowy winters up north, caribou subsist on hair lichens – at times the only food source that remains accessible above the deep snow. Closer to home, mule deer, white tailed deer, mountain goats, elk, moose and even pronghorn antelope munch on lichens, mostly during winter but also at other times. Many invertebrate organisms, such as mites, springtails, snails and slugs, eat lichens as well. In addition, many species of birds and animals that live in trees, like squirrels, use lichens as nesting material for insulation, support or camouflage. People also value lichens. Cultures all around the world have harvested lichens for food, clothing, dyes, perfumes, medicines, poisons and decorations.

Here in Montana, we are blessed with diverse and healthy lichen populations. In general, lichens are very sensitive to their environment, reacting both to the type of forest they inhabit and the quality of the surrounding air and water. In the eastern United States, for example, acid rain exterminated many species that only now are starting to re-colonize their former ranges. Here in Montana, we have been fortunate to have incurred less environmental damage. Also, we are situated in a region of converging ecological and climatic zones. We have a Pacific Northwest influence coming from the west, a great basin/desert influence to the south, a prairie influence from the east and a sub arctic influence traveling down our mountain ranges from the north. Furthermore, our geologic history has provided a complex landscape that hosts unique lichen floras. Some species only live on siliceous rocks (sandstones, granites), while other species live only on calcareous rocks (limestones, dolomites). In Montana, we have plenty of siliceous rocks, like those of the Belt supergroup of western Montana, and plenty of limestone rocks, such as the Madison formation found in the Bob Marshall Wilderness, Little Belt Mountains, and others. We also have plenty of areas that have been affected by glaciers, which just mixed everything up. These factors, coupled with our relatively pristine environment, provide us with many lichen-rich ecosystems to explore.

Here are a few tips for lichen-hunting. On trees, keep an eye out for the bright yellow wolf lichen (Letharia vulpina), once used to poison wolves; the brown-eyed sunshine lichen (Vulpicida canadensis); the grey hammered-shield lichen (Parmelia sulcata); the grey-green forking bone lichens (Hypogymnia); horsehair lichens (Bryoria); and old man’s beard (Usnea). On the ground, look for trumpet-shaped pixie cups (Cladonia) and the flat, often-furry dog pelts (Peltigera). On rocks, search for brightly colored crust lichens like the yellow map lichen (Rhizocarpon geographicum), or the foliose orange sun lichens (Xanthoria) and the grey-brown belly button lichens (Umbilicaria).

Although often small and easily overlooked, these fascinating organisms are a significant part of Montana’s natural heritage. Lichens can be enjoyed anytime of the year, so the next time you’re out and about, keep your eyes peeled, get on your hands and knees, and you shall not be disappointed.

Tim Wheeler is a geologist, outdoor photographer, and lichen enthusiast who lives outside Arlee.

This article was originally published in the Winter 2005-2006 issue of Montana Naturalist magazine, and may not be reproduced in part or in whole without the written consent of the Montana Natural History Center. ©2005 The Montana Natural History Center.

Click here to read more articles from Montana Naturalist magazine.

Want to learn more about our programs? Sign up for our e-newsletter! You can also become a member and get discounts on our programs as well as free reciprocal admission to 300+ science centers in North America!