River Otters

by Anna McNairy

Broadcast 3.6 & 3.11.2016.

Photo by Dmitry Azovtsev (CC-BY-SA-3).

Listen:

At the end of last summer, as I sat in an eddy on the Clark Fork River, something furry and black caught my eye, moving as smoothly as the water itself. I was looking at a North American river otter. Remembering studying sea otters in elementary school, I wondered if I had just seen something rare for this region, and decided to do a little research.

What I found has convinced me that seeing the North American river otter was a treat. Although its population is on the rise in Montana, it has suffered major losses due to pollution and over-trapping. The otter is considered an indicator species: studying its populations helps scientists evaluate the overall ecological health of a given river.

But there is more to discover about a river otter than its population. It can swim up to six miles per hour, can dive down to 60 feet, and can hold its breath underwater for up to four minutes.

Researchers have found ancient otter remains dating back to 200 B.C.E., suggesting that, over the centuries, moving between water and land, the river otter has created a niche for itself. Looking closer, a unique set of adaptations has helped the otter thrive.

When it dives, valve-like skin flaps cover the otter’s ears and nostrils, protecting these sensitive organs. Its eyes are located near the top of its skull so that it can see above the water’s surface while it skims along the waterline.

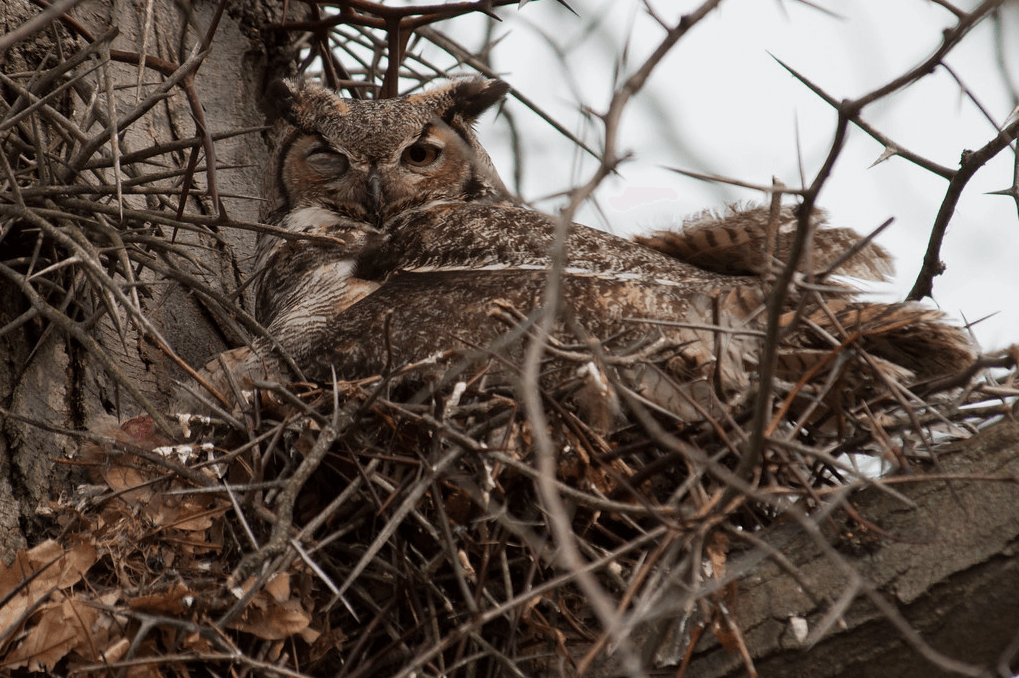

Otters, beavers, sharks, owls, cats, and seals share an adaptation called a nictitating membrane, which looks like a clear third eyelid. As an otter swims, these membranes stay closed, protecting its eyes from incoming particles and improving its underwater vision, just as humans see better underwater while wearing goggles.

When it’s busy spending minutes at a time underwater, fishing or playing, a river otter is also reducing circulation to its limbs, conserving the oxygen in its blood. It can slow its heart rate from around 170 beats per minute down to 15 to 20 beats! Once back on land, the otter resumes its regular heart rate.

An otter’s long, sleek body is shaped for efficient swimming. In the water, its webbed back feet give it speed, and its long tail becomes a rudder. But otters are not water-lovers from birth. In spite of their status as champion swimmers, mothers must drag their pups into the water to teach them how to swim.

The river otter’s long, sleek body helps make it an efficient swimmer. Photo by Cacophony (CC-BY-2.5).

Otters are some of the most playful creatures on the planet. They toss rocks, make diving games, slide over mud and snow on their bellies, and even play games of tag and hide-and-seek. In addition to the adaptations to its nose, ears, throat and body, perhaps its playful personality has helped keep the river otter alive and flourishing over time.

Every week since 1991, Field Notes has inquired about Montana’s natural history. Field Notes are written by naturalists, students, and listeners about the puzzle-tree bark, eagle talons, woolly aphids, and giant puffballs of Western, Central and Southwestern Montana and aired weekly on Montana Public Radio.

Click here to read and listen to more Field Notes. Field Notes is available as a podcast! Subscribe on iTunes, Google Play, or wherever you listen to podcasts.

Interested in writing a Field Note? Contact Allison De Jong, Field Notes editor, at adejong [at] montananaturalist [dot] org or 406.327.0405.

Want to learn more about our programs as well as fun natural history facts and seasonal phenology? Sign up for our e-newsletter! You can also become a member and get discounts on our programs as well as free reciprocal admission to 300+ science centers in North America!