By Rosie Costain, VNS Volunteer

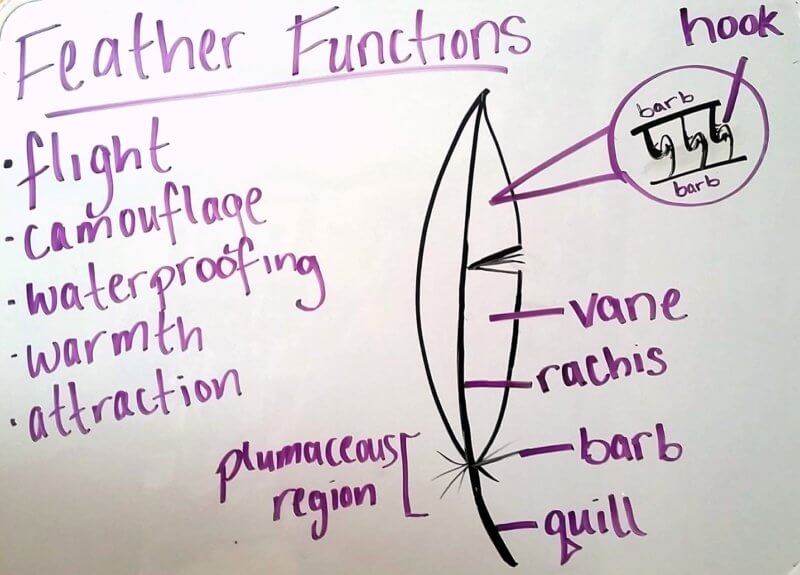

March’s Visiting Naturalist in the Schools lesson was all about feathers. Fourth and fifth graders learned how to identify feathers based on their shape and determined each feather’s function, whether it was the warmth of downy feathers or the assistance in flight of tail feathers.

As we went through the lesson, students asked a lot of questions about bird adaptations. Some of their questions stumped everyone in the room. We came up with the best answers we could through discussion between the teachers and students. But I wanted to find out a bit more.

Here are a few of their questions, with answers based on the best of my researching abilities.

Why do birds have hollow bones? Do all birds have hollow bones?

Birds’ skeletons have a few unique adaptations to make flight possible. One of these is hollow bones.

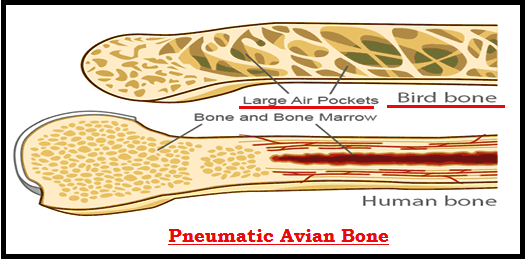

First, let’s talk about what hollow bones do. Hollow bones are also called pneumatized bones, meaning they’re filled with space for air. It is thought that this structure helps with oxygen intake during flight. Air sacs are attached to the hollow areas in a bird’s bones. Essentially, their lungs extend throughout their bones. This helps birds take in oxygen while both inhaling and exhaling. This adds more oxygen to the blood, providing a bird with extra energy for flight.

But hollow bones don’t make a bird lighter, as is commonly thought. According to a researcher from the University of Massachusetts Amherst, bird bones are heavier than animals of similar size. If you compare just the bones, the skeleton of a two-ounce bird is heavier than the skeleton of a two-ounce mouse. A bird’s bones are denser. This density makes these thin, hollow bones stiffer and stronger to keep them from breaking. Crisscrossing struts or trusses also provide structural strength.

A few other fun facts:

- Birds from chickadees to Sandhill Cranes have hollow bones. Not all bones in a bird’s body are hollow, though, and the number of hollow bones varies among species. Large gliding and soaring birds tend to have more, while diving birds have less.

- Penguins, loons, and puffins don’t have any hollow bones. It’s thought that solid bones make it easier for these birds to dive.

- Flightless birds do have hollow bones. Ostriches and emus have hollow femurs. It’s thought that the air sac system that extends into their upper legs is used to reduce their body heat by panting.

- This bone specialization isn’t found only in birds. Fossils show evidence of air pockets in carnivorous dinosaur bones. Humans have hollow bones around their sinuses. They can also be found in the skulls of other mammals and crocodiles.

How can birds lose their feathers and still fly?

Wing and tail feathers are crucial for flight. But what happens when birds lose these feathers?

Constant use and exposure to the elements requires birds to replace their feathers through a process called molting. Replacing feathers takes a lot of energy, so birds typically molt at times when they aren’t doing other high-energy activities, like migrating or nesting. This feather loss can occur gradually or all at once.

Some birds, like ravens, can molt for up to six months, replacing a few flight feathers at a time. They wait until new ones grow in before molting another few. Usually, they’ll lose the same feathers on each wing at the same time, keeping their wings symmetrical throughout the replacement process. Smaller birds do the same thing, but it only takes about two months. This extended molting process allows these birds to fly, despite losing some feathers.

Gliding birds compensate for lost feathers by changing their wing and tail position during flight to remain aerodynamic.

Birds like ducks and loons are too heavy to fly with just a few feathers missing, so they molt all their flight feathers at once, grounding them for about a month. To avoid predators, they stay in or close to water.

What makes feathers waterproof? Are all birds waterproof?

When water falls on a duck’s back, it beads up and rolls off, keeping the underlayers of down dry. In order to stay dry and warm, ducks’ feathers are “waterproof.”

Part of this protection from water comes from a feather’s structure. On a feather, branching out from each side of the rachis (the stiff, stem-like line traveling up the center) are the vanes (the flexible structures that make up the main body of the feather). These vanes are made of individual barbs, which are a bit like individual hairs. But on outer layers of feathers like wing and body feathers, these barbs are attached to each other. On the barbs are barbules that hook each barb together, like Velcro. This structure helps keep some water out and warmth in, giving some protection from water but is similar to wearing a windbreaker in a rainstorm. But there are extra measures that keep birds dry.

Bird feathers aren’t naturally completely waterproof. Birds are constantly grooming, or preening, themselves. While preening, birds remove dirt, dust, and parasites from their feathers while also straightening feathers to their best shape and position. For some birds, like ducks, the uropygial gland, or preen gland, is an essential part of the preening process. The preen gland is found near the base of the tail and produces an oily substance that waterproofs feathers. When preening, birds evenly spread this oil to coat and protect each feather. This allows ducks to comfortably float on water all day and allows Osprey to dive into water for fish.

Not all birds are waterproof. Owls, pigeons, parrots, and hawks don’t have a preen gland. Instead, they have powder down feathers. These specialized feathers disintegrate into tiny particles of keratin forming a fine powder similar to talcum powder. The powder is slightly oily and sticks to the feathers, helping keep some water away. These birds are less likely to completely immerse themselves in water, so they don’t have the level of waterproofing that waterfowl require.

Despite waterproofing efforts, some birds need to take an extra step when they get wet. Cormorants can often be seen holding out their wings in the sun. These aquatic birds aren’t as waterproof as ducks. The extra weight from waterlogged feathers helps with diving (a cormorant specialty). But because their feathers get so wet, cormorants have to spread out their wings to dry. Other birds that lack a certain amount of waterproofing can be found doing the same thing when they get wet.

Double-crested Cormorant drying its wings in the sun. Photo by Allan Hack, CC 2.0.

Click here to read more from our Naturalist Blog.

Want to learn more about our programs as well as fun natural history facts and seasonal phenology? Sign up for our e-newsletter! You can also become a member and get discounts on our programs as well as free reciprocal admission to 300+ science centers in North America!